.

1. Design and Nature:

Design is implicit in nature in even its simplest forms. People are conscious of the beauty of a flower, a leaf, or a seashell, the wonderful world of the microscope is frequently familiar only to the scientist.

Through magnifications we discover the most fundamental truths about design and many of the most fascinating patterns and space relationships existing everywhere.

Fern Sporangium, when viewed through a microscope, reveals its circular motif.

2. Rhythm:

Any good design is based on some sort of rhythm, and the realization that not only the animal kingdom but also the plant and mineral world ebb and flow in a constant yet flexible rhythmic pattern.

2.1 Seasonal and Lunar Rhythm:

We take for granted the rhythm of the seasons. The pattern of life has revolved around an eternally recurring cycle of spring festivals celebrating the sowing of seeds, harvest celebrations in honor of the reaping and storing of crops, and winter festivals to relieve the long monotony of the barren months. The rhythm of seasonal change is apparent in landscape and weather.

Seasonal Rhythm:

Scientists have made detailed studies relating migratory patterns of birds with the weather, to the presence of insects and other food in certain areas, and to breeding habits. The routes and destinations are definite and unvarying for the most part, related to the changing seasons. Some birds like geese and some ducks need some cold snowy weather to let them know it’s time to go.

Lunar Rhythm:

The relation of moon and tides has long led to theories about the effects of the moon upon human events. It’s quite possible that much of the folklore may have valid bases stemming from the close associations of primitive people with nature and their observation of and dependence upon cycles that tend to go unobserved in mechanized modern life.

Daily Rhythm:

The rhythms of night and day have varying manifestations. When a bean plant is raised in darkness, it has no daily sleep movement in its leaves; but of exposed to a flash of light, it will show a definite natural reaction. When it is returned to darkness, the pattern remains; every day at the time of that single exposure to light the leaves will persist in elevating.

The fiddler crab starts to turn black at sunrise, wearing a protective cloak against the glaring sun and predators. At sunset it speedily blanches out again to a silvery grey. Even captured crabs, when kept in a dark room, will continue to exhibit this natural rhythm.

Many animals emerge towards evening to seek water and food or, in the case of the beaver, to work on their dams and lodges. Some of these patterns are conditioned by the presence of man or traffic during the day. Even in isolated regions a natural rhythmic pattern can be detected among various species.

2.2 Man and Rhythm:

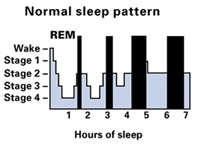

From his first heart beat, man is a creature of cycles – of the rhythmic contraction of the heart known as systole and diastole, of the beats of his pulse, of the regularity of breathing, of waking and sleeping, of eating and fulfillment, of activity and rest. His reproductive processes follow set patterns of fertility and sterility and his gestation period forms a precise design of development that can be clearly charted from month to month.

Primitive man's first expressions were his beating on a simple drum of animal skins, dancing to this beat, and chanting in monotonous rhythms.

African traditional drum beating.

Gradually the structure became more complex, with narrations of events evolving into dramatic enchantments and with new instruments added to accompany the drums.

Modern Brazilian drum beating.

Graphic expression follows much the same patterns. The Electrocardiogram presents a definite relationship of natural rhythms to graphic representation. These are rhythms made unconsciously by man, designs based on the rhythms inherent in human life.

3. Variety:

The existence of rhythm ensures variety, for it is the contrast of light with dark, of winter with summer, of height with depth, and of loud with a soft beat that makes for the rhythmic pattern. The green tree is enhanced by the tracery of black branches through its leaves. The variations in flowers, rocks, seashells and butterflies have caused people to travel the world over in search of specimens.

3.1 Variety in Shape and Size:

The most obvious variations found in nature are those in size and shape. In an area so small that it might well go unnoticed; the Japanese create an atmosphere of tranquil beauty. The Japanese landscape designer ensures that his surroundings are designed to look uncultivated and natural thereby achieving unity with nature – the essence of good design.

Dramatic variations among trees can also be noted. A field of daisies is interesting owing to a wide variation in scale, from tiny flowers half hidden in the grass to the largest ones with their prominent button centers. No area of grass between the clumps of flowers is of the same size and shapes as any other area.

In astronomy, one finds similar variety of size and spacing. Although at a distance many stars may seem alike in size, the aspect of the heavens as a whole is one of infinite variety in distribution and brilliance.

3.2 Variety in Color:

The best way to appreciate variation in color is to attempt painting a landscape. One may discover the infinite variety and subtlety of nature's greens; not only the differences between the green of leaves or grass but of various areas within the leaves and grass, where a ray of sunlight brightens or a cloud shadow makes the green darker and cooler.

The sky offers another pitfall, for there is no surer sign of an amateur painter than the garish blue of the sky he paints. To produce a sky with the convincing look of nature requires great subtlety and a willingness to see that what one may conventionally think of as blue is often green or rose. While color in nature is all round us, there is much that is hidden from us – not by outward circumstance but by own blindness and preconceptions.

3.3 Variety in texture:

The exploration of texture is one of the major adventures in the artist's study of nature. Texture has two dimensions: tactile quality and visual quality. The tactile quality can be felt and appreciated with the fingers, like the ridges on the leaf shown in the image here. In design the tactile quality often comes from the nature of the material used, such as the roughness of a stoneware jar or the nubbiness of a tweed fabric, and a good designer takes his textural effects from the material itself.

Weathering is a great creator of texture in nature. Sometimes in the case of stones, old stumps, or metal, visual textures created by the elements remain after tactile textures have disappeared under the polishing action of the wind, rain, sun and snow. Spheroidal weathering of sandstone at Mt. Vesuvius.

Leaves attacked by insects develop fascinating patterns as their cells disintegrate.

Feeding pattern of a caterpillar.

4. Balance:

Variations in size and shape, and in texture provide esthetic balance to the natural environment. The presence of bright color as an accent in the stretches of green field, forest, and the blue sky is nature’s way of counteracting great cool areas with small bits of exciting colors. This is balance.

Examples of Nature’s balance:

• The rough bark of a tree is balanced by the smoothness of its leaves.

• Smaller flowers frequently have the greatest fragrance.

• The porcupine has his protective quills, and the skunk his offensive odor, and tiny insects have a potent sting to compensate for their lack of size and ferocity.

• In human life, after every inhalation, comes exhalation; days of activity are followed by nights of rest.

5. Form:

The world around us is composed of forms, each with individual characteristics. Trees, which from a distance look flat, when approached become three-dimensional forms that can be walked around and viewed from all sides. The contour of the land is a flattened shape at sunset from behind, but as one moves across it, he finds himself surrounded by hills and hollows, that is, by forms. Even a blade of grass has form when it is handled or blown through to make a sound. Nature embodies all her animal life in form, from man to the so-called “shapeless” jellyfish. Form is involved with mass or volume, but it goes further. Mass or volume is delimited by shape and is contained by size, thereby becoming the form of the object.

6. Unity:

Nature, in all its parts, demonstrates a certain fundamental similarity.

• The life rhythms occur in weather, in the seasons, and in man – are all interrelated.

• The rotation of the electrons around the nucleus is similar to the ordered movement of infinite galaxies orbiting the universe.

The cycle of creation and disintegration illustrates the great basic fact of nature, the characteristic overall relationship of elements identified as Unity, or harmony. As physicists and other physical and biological sciences point more and more toward the oneness of the universe, one realizes that this is what philosophers have been trying to convey for centuries.

7. The Creative Artist:

The four principles found in nature and their resulting unity can be valuable guides to the creative artist as he strives to improve or interpret what he finds. This unity of rhythm, variety, balance and form comprises the essence of the universe. Appreciation of this essence and application of the four principles can help the creative artist make a meaningful contribution to the field of design.