The sustainability idea is both very ancient and quite recent. Before consumerist modern era, most cultures lived in harmony with nature, their lifestyles, rituals and behaviour aimed for stability and continuity. However, the inevitable change happened in the rising global economy – it led to an industrial consumerist mono-culture that resulted in persistence of desperate poverty along with deep disparities as well as proliferation of risky technologies and degradation of essential ecosystems. However, realizing the environmental threats, real or potential, to the quality of life, environmental movements have begun in virtually all sectors of industrialized countries, including business, manufacturing, transportation, agriculture, and architecture. The critics pointed out to the fact that economic growth is not open-ended and that it has failed to deliver benefits where they were most needed. In last few decades, numerous reports, studies, theses, articles and books have been published documenting impacts and opportunities, e.g., species loss, resource constraints, and business opportunities for those aware of sustainability issues. There was general agreement in the scientific community that things need to change, and this is often discussed under the term "sustainability."

From Product to System and Services:

Pursuit of sustainable development requires a systems approach to the design of industrial product and service systems. Although many business enterprises have adopted sustainability goals, the actual development of sustainable systems remains challenging because of the broad range of economic, environmental and social factors that need to be considered across the system life cycle. Previous work on sustainable design has focused largely upon ecological efficiency improvements. For example, companies have found that reducing material and energy intensity and converting wastes into valuable secondary products creates value for shareholders as well as for society at large. To encourage broader systems thinking, the new design protocol involves the following steps: identifying system function and boundaries, establishing requirements, selecting appropriate technologies, developing a system design, evaluating anticipated performance, and devising a practical means for system deployment. The approach encourages explicit consideration of resilience in both engineered systems and the larger systems in which they are embedded. Sustainability is often misinterpreted as a goal to which we should collectively aspire. In fact, sustainability is not an end state that we can reach; rather, it is a characteristic of a dynamic, evolving system. And system thinking offers a potential means to overcome the above barriers.

A product, process, or service contributes to sustainability if it constrains environmental resource consumption and waste generation to an acceptable level, supports the satisfaction of important human needs, and provides enduring economic value to the business enterprise. Note that a product cannot be sustainable in an absolute sense; rather, it must and the natural environment. Therefore, the key practical challenge of sustainable design is to understand how products, processes, and services interact with these broader systems.

Product Service Systems, put simply, are when a firm offers a mix of both products and services, in comparison to the traditional focus on products. As defined by (van Halen, te Riele, Goedkoop) "a marketable set of products and services capable of jointly fulfilling a user's needs". PSSes can be realized by smart products.

The initial move to PSS was largely motivated by the need on the part of traditionally oriented manufacturing firms to cope with changing market forces and the recognition that services in combination with products could provide higher profits than products alone. Faced with shrinking markets and increased commoditization of their products, these firms saw service provision as a new path towards profits and growth. While not all product service systems result in the reduction of material consumption, they are more widely being recognized as an important part of a firm's environmental strategy. In fact, some researchers have redefined PSS as necessarily including improved environmental improvement. For example, PSS can be defined as "a system of products, services, supporting networks, and infrastructure that is designed to be competitive, satisfy customers' needs, and have a lower environmental impact than traditional business models".

Types of PSS:

There are various issues in the nomenclature of the discussion of PSS, not least that services are products, and need material products in order to support delivery however, it has been a major focus of research for several years. The research has focussed on a PSS as system comprising tangibles (the products) and intangibles (the services) in combination for fulfilling specific customer needs. The research has shown that manufacturing firms are more amenable to producing "results", rather than solely products as specific artefacts and that consumers are more amenable to consuming such results.

This research has identified three classes of PSS:

• Product Oriented PSS:

This is a PSS where ownership of the tangible product is transferred to the consumer, but additional services, such as maintenance contracts, are provided.

• Use Oriented PSS:

This is a PSS where ownership of the tangible product is retained by the service provider, who sells the functions of the product, via modified distribution and payment systems, such as sharing, pooling, and leasing.

• Result Oriented PSS:

This is a PSS where products are replaced by services, such as, for example, voicemail replacing answering machines.

‘Product Service Systems (PSS) are not a new idea but if used intelligently can offer significant benefits to all parties. For example, the manufacturer might manufacture photocopiers and loan them to businesses that then pay for the service of photocopying. The customer gets good value for money by only paying for the service that they want, and need not worry about maintenance of the copier, which is taken care of by the manufacturer. The manufacturer never loses ownership of the copier and the business is no longer tied to manufacturing and selling photocopiers. They have an incentive to maximise the life of their products and re-manufacture/recycle old or broken models’.

www.espdesign.org

Eco Design, D4S [design for sustainability], LCM [life cycle management]:

As a brief history, in the 1990s, concepts such as Ecodesign and green product design were introduced as strategies companies could employ to reduce the environmental impacts associated with their production processes. These strategies also served to bolster a company’s position and competitive edge in a market where more and more emphasis was being placed on environmental stewardship. In 1997, UNEP published “Ecodesign: A Promising Approach to Sustainable Production and Consumption” which was one of the first manuals of its kind and helped lay the foundation for widespread adoption of Ecodesign concepts. This publication introduced the fundamental concepts of Ecodesign to policy makers, programme officers, and project specialists. Like many other environmental concepts, Ecodesign has evolved to include both the social and profit elements of production and is now referred to as sustainable product design.

The concept of ‘Design for Sustainability’ (D4S) requires that the design process and resulting product take into account not only environmental concerns but social and economic concerns as well. The D4S criteria are referred to as the three pillars of sustainability - people, profit and planet. D4S goes beyond how to make a ‘green’ product and embraces how to meet consumer needs in a more sustainable way. Companies incorporating D4S in their long-term product innovation strategies strive to alleviate the negative environmental, social, and economic impacts on the product’s supply chain and throughout its life-cycle.

Mere a ‘Greenwash’?

Though sustainability is slowing building up as a new culture, there are several attempts to mere greenwash the whole ideology. Greenwash is a term used to describe the perception of consumers that they are being misled by a company regarding the environmental practices of the company or the environmental benefits of a product or service. It is a deceptive use of green marketing. A 2010 study by Terrachoice, an independent testing and certification organisation revealed: out of 5296 products only 265 were really as green as they claimed – 95% of the ‘green’ products are being greenwashed.

In December 2007, US environmental marketing firm TerraChoice gained national press coverage for releasing a study called “The Six Sins of Greenwashing,” which found that more than 99% of 1,018 common consumer products randomly surveyed for the study were guilty of greenwashing.

The 6 Sins of Greenwashing (PDF)

According to the study, the six sins of greenwashing are:

• Sin of the Hidden Trade-Off:

E.g. “Energy-efficient” electronics that contain hazardous materials. 998 products and 57% of all environmental claims committed this Sin.

• Sin of No Proof:

E.g. Shampoos claiming to be “certified organic,” but with no verifiable certification. 454 products and 26% of environmental claims committed this Sin.

• Sin of Vagueness:

E.g. Products claiming to be 100% natural when many naturally-occurring substances are hazardous, like arsenic and formaldehyde (see appeal to nature). Seen in 196 products or 11% of environmental claims.

• Sin of Irrelevance:

E.g. Products claiming to be CFC-free, even though CFCs were banned 20 years ago. This Sin was seen in 78 products and 4% of environmental claims.

• Sin of Fibbing:

E.g. Products falsely claiming to be certified by an internationally recognized environmental standard like EcoLogo, Energy Star or Green Seal. Found in 10 products or less than 1% of environmental claims.

• Sin of Lesser of Two Evils:

E.g. Organic cigarettes or “environmentally friendly” pesticides. This occurred in 17 products or 1% of environmental claims.

The 2007 list had only six sins. Things, it seems, have gotten worse and a seventh sin, the Sin of Worshipping False Labels, emerged in the 2009 survey.

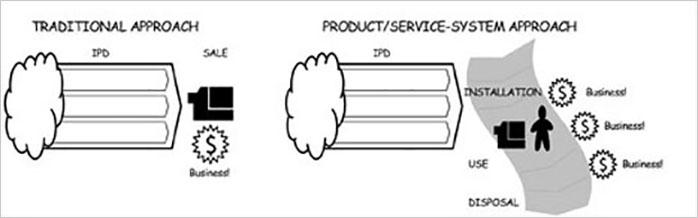

The figure shows the traditional approach, where the value creation process ends with the sale of the product, and the PSS approach, where the value creation process continues throughout the product's life.

Source:

Tan, A. R., McAloone, T.C., Gall, C. (August, 2007) Product/Service-System Development – An Explorative Case Study In A Manufacturing Company International Conference On Engineering Design, Iced’07, Cite Des Sciences Et De L'industrie, PARIS, FRANCE Figure-1.

Available at: http://www.producao.ufrgs.br/arquivos/disciplinas/508_pss2p_334.pdf