With its strangely attractive land encompassing extremes of geography and climate, colour has always been an intrinsic facet of Rajasthan. In its art and architecture, in its rites and rituals, and in the clothing of its people, colour symbolically represents the life-spirit in a myriad of forms and shapes.

Rajasthan has played an important role in the history and developments of Indian art from the earliest times. The Rajasthani genius was at work in the Ghaggar basin in the northwest, where the Harappan civilization flourished. It was at work also in the Chambal valley to the east, where numerous caves and rock shelters with prehistoric and early historic paintings have come to light.

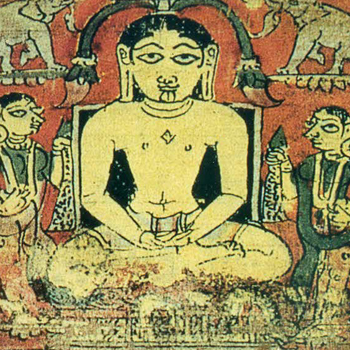

The tradition grew vigorously in everyday rituals, in the embellishment of dwellings and household objects, and in the illustration of palm-leaf manuscripts. Illuminated manuscripts and painted manuscript covers dating to the eleventh century are preserved in the Jain repositories at Jaiselmer. Contemporary texts like the Kuvalayamala Kaha, written in A.D. 778 at Jalore, tell us about wall paintings that existed at that time. The palm-leaf manuscripts of Ogha-Nirukta and Dasa-Vaikalika-Tika copied in 1060, followed by Savaga-Padikkamana-Sutta-Chunri painted in 1260 at Aghata, modern Ahar in Udaipur, under the Guhila king Tejsimha, gave place to numerous paper manuscripts prepared in the following centuries. References to wall paintings have also been found in an account of Sultan Jala-ud-din Khalji's Rajasthan conquest between A.D. 1290 and 1296.

This period was followed by one of the most confused political environments, and it is difficult to identify the painting styles that flourished in different parts of the state. Some scholars attribute the paintings of the Chaurapanchasika and the Laura-Chanada manuscripts and the distinct style of these and some related paintings to the Mewar-Malwa region. In view of the fact that paintings—both mural and miniature—are produced at Chavand, Chitor, and some other centres of Mewar, the possibility of the latter, with its rich cultural, literary, musicological, and religious attainments, being a strong centre of art activity cannot be ruled out.

The socio-cultural development of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries provided an ideal background for the growth of flourishing schools of painting. Painters took delight in drawing colourful paintings of Radha and Krishna from Jayadeva's Rasikapriya. Romance and poetry also dominated the literary and artistic creations, and many sets of Ragamala (visually depicting musical modes) or Nayaka-Nayika Bheda (the moods of the hero and heroine) or Baramasa (paintings depicting the characteristics of the twelve months) were produced.