Product Design

Batch 1987-1989

(13 items)

Product DesignBatch 1987-1989

(13 items)

(13 items)

by Prasad Boradkar

This project's goal is to investigate the relationship between space, time, and music. An attempt is made here to briefly show how space and time are used to advantage in music and how music is modulated to create effects of space and time.

There can be two distinct approaches for conducting this type of study. One would entail selecting a specific musical form, such as rock music, Hindustani classical music, folk music, or any other, and then studying how spatial and temporal effects are created in that musical form. This would require a thorough study of that particular form of music and access to a large number of compositions in that style.

The other approach would be to keep the spectrum of music choices wide and demonstrate through various forms of music how spatial and temporal effects are achieved. The method followed here is the second, as the first necessarily requires extensive knowledge of one particular form of music. These ideas and interpretations are personal and thus highly subjective.

by Anil Kumar Gupta

Drinking tea has become a ritual. Tea has become a "social drink" and is consumed in enormous quantities. Surprisingly, about 350 litres (3600 cups) of tea are consumed every day in IIT during the working hours (9 a.m.–5 p.m.).

During these hours, no one is officially permitted to discontinue his work and go for tea. But almost as a ritual, most people drink tea twice a day between 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Do we consume tea only for its warm, stimulating effect, or do we have other reasons too? This inexpensive drink has so widely influenced people that it drives hordes of them towards itself throughout the day. Someone has aptly commented that IIT is engulfed by a "tea phenomenon." This is an attempt to look into this "phenomena." It seems futile to convince people that it is a waste of time (if one thinks so). It would be preferable to understand what people want and to provide them with certain basic amenities so that time is not wasted in this process (tea drinking).

Though the study could be done for the amount of tea consumed in 24 hours in the whole of IIT, we have decided to limit ourselves to studying this "phenomenon" only between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. The study will also be limited to the working areas (administrative and academic) of IIT and not include residential areas.

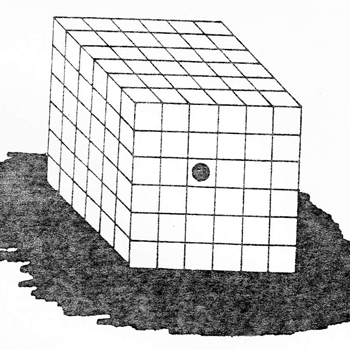

by J. Bhaskar

-Better Communication

-Training of managers

-Teaching of abstract concepts.

Here an attempt has been made to develop visual symbols for various terms associated with assets and liabilities that are commonly used in a business management situation.

by K. Puhazhendi

The robotic finger is an end effector, which is called a gripper. The gripper is the device mounted at the distal end of a robot arm, enabling it to pick up workpieces and hold, manipulate, transfer, place, and release them accurately in a discrete position. Thus, the gripper is an all-important mechanical interface between the robot and its environment, without which, in many circumstances, the robot cannot function effectively, irrespective of the degree of sophistication it may otherwise possess.

The project consists of two parts, namely, a study of existing gripping mechanisms. The goal of this work is to provide the designer with a database of various gripping mechanisms and their related biological mechanisms so that the designer can link the two approaches to solve specific gripping problems. This is done by giving a rough classification based on various parameters like type of mechanism, scope of utility, etc., of available gripping mechanisms and certain biological grippers. A study of their operation is provided to help the designer understand the fundamentals and develop his own classification methodology suitable for his applications.

by Madhuri Vetsa

-Product conceptualization

-Drawing

-Prototyping

-Mould making

-Final Production

Once upon a time, the whole process was solely controlled by people and machinery, but now computers are extending their utility to these areas as well by having CAD for engineering drawings and CAM for manufacturing processes. However, there has been no such computer input at the product conceptualization level, which is the stage in which the designer has the most creative involvement. It is at this stage where the problem is understood, decisions are taken in terms of volume, size their shape and finally decisions of details, graphics and colours etc. This lack of computer support and help in this area drew interest, and thus this became the area of concentration for this study.

by N. Prasad

A child, with the assistance of its parents, starts recognising things around him. He starts developing his own vocabulary and, within a short time, starts identifying the objects correctly. He can recognise a car as a car, a cow as a cow, a TV as a TV, a shop selling ice cream, etc. The children of these days are even smarter; they are able to operate a TV, a tape recorder, a VCR, etc., which were unheard of by an adult some 15 years ago.

We can judge the capacity and capability of the human brain if a child can correctly recognise everyday objects, even as more and more new objects are introduced. It assigns different meanings to different objects and helps to differentiate clearly between two types, two classes, or two families of objects.

The number of products that are being introduced into the market is increasing day by day. These products were designed to meet basic and higher needs, as well as some that were designed to meet very minor human needs. People can clearly identify the product or recognise the class or family to which the product belongs.

The degree to which the product is recognised depends on several factors: the person's value system, cultural background, relationship with the product, environment, and other demographic and psychographic factors related to the person recognising the product.

by Ramamurthy Shastry B. G.

Computers and their applications have evolved along with storage media and their capabilities. Every time the storage density increased, it resulted in new applications with better and better facilities for the users. While the first computers occupied the space of a room with very few arithmetic and logical functions, the latest personal computers with portability (less than the size of a briefcase) can do better than big minicomputers.

The following table provides a summary of some of the characteristics of personal computer storage media, both currently available and under development. But it is to be noted that no one medium suits all applications, nor can one generalise the suitability of a particular medium to a specific environment. Each has its own advantages and limitations.

by Rashmi Gothi

If we were to observe all the columns that exist in Hindu architecture lined up in one long row, we would be overawed by the countless forms their outlines define, fascinated by the range and complexity of motifs that adorn their narrow surfaces, and confused as our minds would attempt to segregate and find connections so as to absorb the essence of these unique structures. The richness of motifs and forms is exemplified on the one hand by the surrounding structure, which offers an immediate context, and also by the fact that the information these forms communicate is at varying levels of obvious and symbolic. The variations result from a well-thought-out, predetermined principle rather than a mere juggling of shapes and images. The perfection of form here does not mean a display of physical beauty, but the adequacy of compositional outplay to the significance and inner meaning of the image.

In hindu symbology, the straight is considered active and dynamic. It penetrates, cuts, divides, and disrupts. The movement of the straight line runs into infinite space. It is bodyless and limitless. The forms predominant in the vertical axis are regarded as being in the nature of fire and standing for divine aspirations and illumination. They are imagined to rise upward, raising the spirit of the beholder towards a vision of divine truth.

Hence the column is accorded great importance in Hindu architecture, symbolising as it does a structure that was built to transcend the space and time in which it was erected.

by Ravi T. Reddy

Papier mache is a modelling material consisting of a mash of paper used with a binder and moulded round a shape to make functional and decorative objects. It is a cheap and easy material to use and has the advantage of drying naturally to a hard and durable substance without necessarily having to be baked like clay.

This craft of making objects is an ancient one. Soon after the Chinese discovered how to make paper, 2000 years ago, they began to experiment with papier mache. The interest in this craft declined for hundreds of years until the French revived it in the 18th century. They called it "papier mache," meaning literally chewed up paper. They used it to make trays, boxes, and even furniture that was often inlaid with mother of pearl.

India also boasts of a papier mache tradition. Especially so in the Kashmir region, where highly finished decorative articles like small boxes and containers are made. Papier mache craft forms are an important part of Kashmiri handicrafts. Traditionally, in rural areas, they are sealed with papier mache. This both seals the tiny holes in the container and strengthens it.

by Shah G. A.

Thinking is central to human existence. It is not only habitual; it is compulsive. We gather information from the environment with our senses and process it. Thus, in essence, thinking is information processing. It requires words, abstract concepts, and images. When we think using words – as we almost always do – we are indulging in verbal thinking. This is characterised by inner speech. Thinking with abstract thinking When thinking involves visual images, it is called visual thinking.

Visual and verbal (or abstract or mathematical) thinking are complementary by virtue of their differences in structure. Verbal and mathematical symbols are strung together linearly in conventional patterns such as those afforded by grammar. Mentally tracking these linear structures automatically enforces certain thinking patterns. By contrast, visual thinking is wholistic, spatial, and instantly capable of all sorts of unconventional transformations and juxtapositions. This is because visual thinking involves images that are not exact replicas of reality. These images are a highly personal creation and are more flexible and encompassing than any reality. Visual thinking is a very powerful thinking tool because of its flexibility. It can be immensely helpful in creative thinking because of the innumerable possibilities of transformations.

Visual thinking pervades all human activity. Most memory systems rely heavily on visualization. Designers, engineers, and architects use it most often. Athletes often visualise scenes during practice. Physicists exploring the world of atomic and subatomic phenomena use it. Surgeons think visually while performing operations. Carpenters and mechanics use it to translate plans into actions. Unlike verbal and mathematical thinking, visual thinking is laden with sensory content, which leads to pleasurable experiences.

by Suresh G. Bhat

What is movement, and how does one perceive it? One generally defines movement as a change in position. This, however, is an incomplete definition in and of itself, despite the fact that the other part is generally implied. Movement (of an object) is a change in its position with a change in time. We generally perceive movement through our visual receptors. The other sensory modes can also help in the perception of movement by receiving relevant stimuli that are then properly interpreted by the brain.

Visual perception, which is the major mode of observing movement, itself is possible only if there is relative movement between the object and the eyes. Even when we view stationary objects, the eyes vibrate so as to shift the image in order to receive the necessary stimulus. It is the brain that then decodes the visual message to form an image. The movement of any object may therefore be easily perceived.

Visual perception is essentially an educated reaction of the brain. In addition to the basic image formation by virtue of the optical stimulus, the significance of the image is only obtained through acquired pattern recognition and association as a result of continuous training during an individual's growth. Thus, identification of colour, texture, tone, size, depth or distance, and direction are attributes of a trained brain.

by Unmesh Kulkarni

In today’s society, when one wants to get a message across with speed and efficiency, humour could be one of the best tools because human beings react to such a phenomenon willingly and immediately.

In today’s mechanical life of increasing stresses, one needs to relax somewhere, but our environment is getting dominated by modern, similar looking geometric objects like computers. Their aesthetics are dominated by their function, manufacturing capabilities, and the effects of mass production. We are now passing through a phase in which a universal urban culture is emerging. The rise of the middle class has put designers in a challenging position with their changing needs. Objects that are produced appear more sophisticated. If this trait continues, human beings will get trapped in various concentrates and plastic boxes and lose their sensitivity. It is always said that man invented machines to serve him, but day by day, it seems to be happening that he is getting busy serving these machines. It might so happen that human beings become mere automatons.

It is everybody's duty to prevent this. That is why we see that some design movements like "post modern" or "Memphis" were started. They criticise the Bauhaus tendency towards functional products that follow the philosophy of minimal design. Here the design was considered an opportunity for exploration, and many times humour is used effectively.

by Vinayak Nabar

Like explorations of several kinds, an exploration of form has been a journey into the unknown, with a few things heard and read about, a few known inlets with unknown destinations, a few tools and a fragile material, a mind prone to distractions, but also with benevolent guidance from time to time and people to people, and a hand that liked the work. It has also been an exciting journey, full of surprises and both pitfalls and reward.

And the way it happens so many times, one starts in one direction and arrives at a totally unexpected clearing. The jungle that one thought would be full of trees also harboured beautiful animals.

The intention was to explore various aspects of form, using a material with its inherent potentials and limitations and tools that would act as agents of space while carving out one form from another.

The complexity of the process lay in the fact that one had to be simultaneously aware of the clues of a potential form in the material in hand, the minimum essential characteristics of the possible form, the distortions allowable without loss of identity, the possibility of materialisation with optimum efforts, and the integration of finer details with overall form. Additional complexity was imposed by the desire to explore meaningful form by way of the removal of material with minimal or no addition to the basic shell form.