The Indus Valley Civilization, also known as the Indus Civilization, was a Bronze Age civilization in the northern areas of South Asia that lasted from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and from 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE in its full form. It was one of three early civilizations of the Near East and South Asia, along with ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, and the most extensive of the three.

Excavations of Indus towns have revealed a great deal of evidence of creative activity. A variety of different specimens of the culture’s art were discovered, including seals, ceramics, gold jewellery, and figures in terracotta, bronze, and steatite. Such finds are important because they provide insights into the minds, lives, and religious beliefs of their creators and their surroundings.

Animal remains in Indus Valley

The sheer volume and variety of animal, reptile and bird remains found at three sites is staggering, and on the stratigraphic analysis of the area in which they are found allows for a clearer discernment of how patterns of use and consumption may have changed over the course of Indus epochs.

As others have noted of ancient animal remains in South Asia, cattle “constitute the highest percentage among faunal remains at the primary sites and during all phases of the Harappan occupation. It was a major component of the diet. Cattle were kept for primary products like meat and milk”. They were followed in importance by sheep and goats.

Cattle depiction in Terracotta figurines

Over three-quarters of the animal figures are cattle, usually humped bulls and buffaloes. These figurines are generally believed to be zebu cattle, which are depicted in earlier portrayals with painted geometric designs, large abdomens, and splayed legs and augmented with individually attached, and occasionally painted eyes during the Mature Harappan Period. Apart from them dogs, rabbits, pigs, elephants, felines, deer, monkeys, rhinoceroses, elephants, turtles, and birds are also depicted. Birds are pictured in cages in some cases; dogs, lambs, and monkeys wear collars; and cattle, particularly from later eras, are depicted pulling carts with wheels – all of which imply the practise of animal husbandry in Indus culture.

The terracotta figurine on the left is an animal with a double collar ornamentation. The broken projections on the head could be where the ears were or possibly horns. It is not clear if this is a dog or a bull without a hump. The figurine in the center is a one horned rhinoceros and the broken figurine on the right appears to be of a bull with broken leg and horns missing.

- Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, 2023.

(Image source)

What these figurines could have meant?

Researchers think that these animal sculptures were created for ceremonial usage, as children’s toys, or as amulets. A variety of discoveries, including elephant sculptures from Harappa with red and white stripes painted across their faces, support this theory. It has been claimed that such styles of painting may represent a culture of adorning domesticated elephants for ceremonial purposes, as well as the usage of clay figurines for ritual sacrifices rather than actual animals.

Baked clay bull Mohenjodaro C. 2500 B.C.E

(Image source)

An endearing form with plumpish build, elongated figure and innocent face this typical animal is one of the two best known styles of bulls that the Indus artisan innovated. This terracotta bull figurine is entirely handmade with cream slip on it. Probably a knife might have been used in shaping the parts of the body and its minute details. It appears to be wearing a garland or plaited rope around its neck.

During excavation, a large number of small clay figures of cattle were found, as were fragments of small clay carts. Even more common were biconical clay pieces or tokens, with a total of 23,000 recovered. Much like with the human figurines excavated along with them since the 1920s, the terracotta animal figurines from this period provide us with a sense of the relationship between humans and animals during the Indus Valley Civilisation, as well as the broader symbolic and functional position of animals within Indus ideology.

Clay model of cattle pulling a wheeled cart. From the Chanhu Daro, ca. 2250 B.C.

(Photograph courtesy of the University Museum)

(Image source)

The Harappan Gallery houses a limited collection of objects categorised as toys. One figure from Kalibangan in particular has an animal with a moving head that is foxed to the body by a thread. Additional toys include small depictions of carts and possibly ploughs, demonstrating the importance of trade and even agriculture in the town. Because their full-size equivalents are generally lost from the archaeological record, the survival of these ceramic toys is crucial in providing us with insight into such activities.

National Museum, New Delhi - Harappan Artefacts

(Image source)

Apart from the human figures, excavations have uncovered a plethora of clay animal depictions. These animals include a bull, a buffalo, an elephant, a dog, a deer, a monkey, and birds. None of these representations are very naturalistic or artistic and should again appear to be symbolic in nature.

Indus Valley Stamp Seals

The symbolic and formal imagery on the seals are typical of Indus Valley iconography and consist of bovine figures such as bulls, water buffalo, Indian gaur or wild ox and zebu; other animals such as elephants, rhinoceroses, tigers; fantastical creatures such as unicorns (sometimes interpreted to be bovine animals in strict profile) and plants, although less common; and human and human-like figures. Seals frequently included images of individuals appearing to be engaged in religious activities, complemented with themes such as the holy fig, containers, and agricultural equipment. The geometric forms and realistic figurations are nearly usually accompanied with inscriptions of four to seven characters in the as-yet undeciphered Indus script, making the Indus Valley stamp seals the most prevalent group of artefacts to show it.

Front and back of seal with two-horned bull and inscription, Indus Valley Civilization, c. 2000 B.C.E., steatite (Cleveland Museum of Art)

(Image source)

Animal-Human hybrids?

Historically, archaeologists thought the Harappans used cattle primarily as draught animals and as a source of food. (Other major foods grown via cultivation were wheat, barley, peas and beans, and cotton.) It was also clear that animals had a role in Harappan philosophy, since several of the seal-tablets discovered at sites such as Harappa and Mohenjo Daro depict cow-women and maybe a bull-man.

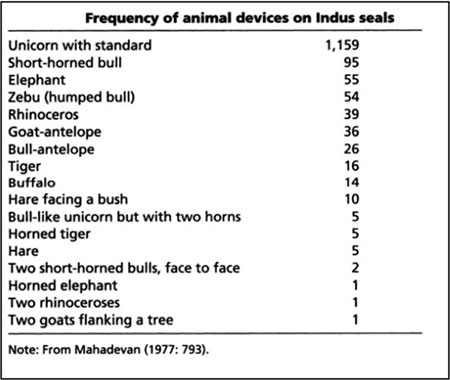

The Unicorn Seals

The Harappan seal-tablets represent a variety of animals, but the most prevalent are eight. Four of these are grassland wild animals: rhinoceros, elephant, buffalo, and tiger. They are in the minority in the seal-tablets sample. The other four animals are domesticated: goat, zebu, shorthorn bullock, and unicorn bull. The latter, actually a profile of an animal akin to the well-known bullocks from Gujarat, is depicted with great frequency, occurring as almost 90 percent of the corpus from any given site. At the back of each seal is a perforated knob or boss that would allow it to be suspended on a string and worn.

Harappan Seals

Thousands of seals have been found so far from excavations at many different Indus Valley Civilization sites. It is thought they played an important role as the mode for transactions, highlighting a vibrant local and long distance trading network.

Unrecognizable Artefacts

Although many animal figurines have identifiable traits (e. g., the applied “hide” and horn typical of a rhinoceros figurine), some figurines are not readily identifiable. Animal figurines that are badly broken are sometimes particularly difficult to identify, but even the more complete figurines are not necessarily recognizable. Perhaps the makers of Indus figurines created abstractions, possibly by emphasizing particular features (as is common in caricatures), that were and are not recognizable to others.

Many archaeological sites have been destroyed or looted, making it difficult to reconstruct a complete picture of the Indus Valley civilization. As a result, our understanding of their society and culture remains incomplete, and many questions about their way of life, beliefs, and practices remain unanswered.

Unidentified animal figurine from Harappa.

(Image source)

Difference between Indus Valley and Bhimbetka art

The Indus Valley Civilization and Bhimbetka both provide valuable insights into ancient Indian art and culture. However, there are several differences between the animal depictions in art in these two regions.

• Time period:

The Indus Valley Civilization existed between 2600 BCE and 1900 BCE, while Bhimbetka is believed to have been inhabited by humans for over 30,000 years. Therefore, the animal depictions in art in Bhimbetka are much older than those in the Indus Valley.

• Style:

The style of animal depictions in the Indus Valley Civilization is highly stylized, with animals being portrayed in a naturalistic yet simplified manner. In contrast, the animal depictions in Bhimbetka are more realistic and detailed, with a greater emphasis on the texture and anatomical features of the animals.

• Purpose:

The animal depictions in the Indus Valley Civilization were primarily found on pottery and seals, and were likely used for religious or ritualistic purposes. In contrast, the animal depictions in Bhimbetka were found in rock shelters and were likely created as part of everyday life, as well as for spiritual and artistic expression.

• Diversity:

The animal depictions in the Indus Valley Civilization primarily feature domesticated animals such as bulls, cows, and goats, while the animal depictions in Bhimbetka are much more diverse and include a wide range of wild animals such as tigers, rhinoceroses, and elephants.

Overall, while both the Indus Valley Civilization and Bhimbetka offer important insights into ancient Indian art, the animal depictions in each region differ in terms of style, purpose, diversity, and time period.