Design Resource

Animal Depiction in Indian Art throughout History

The representation of cattle and its evolution over time

by

Mughal paintings emerged during the Mughal Empire (1526-1858 CE) and were heavily influenced by Persian and European art, as well as Indian art forms. These paintings covered a diverse range of subjects, including historical events, court life, hunting scenes, and portraits of emperors and their families. Mughal paintings were characterized by a more realistic and three-dimensional style, with a greater emphasis on shading, perspective, and depth. The color palette of Mughal paintings was richer and more diverse than Gupta paintings, featuring shades of blues, greens, and gold.

Unlike Gupta paintings, which were primarily focused on religious themes, Mughal paintings explored a variety of subjects and were known for their intricate details and vivid colors.

(Image source)

(Image source - right)

Depiction of everyday life

Mughal paintings often depict scenes from courtly life, such as hunting parties, feasts, and royal processions. They also feature portraits of Mughal emperors, their wives, and other courtiers. In contrast, earlier Indian paintings tended to focus on religious and mythological themes.

The painted world of the Mughals and Rajputs preserves for us extraordinary vivid images of daily encounters, some pleasant and others less so, between humans and animals. The Europeans’ love for cats and dogs is graphically and empathetically portrayed in a meticulously observed, tinted drawing of a banquet scene by an unknown Mughal artist. In contrast to this picture, which is enlivened by a social conviviality and festive spirit, is a more colorful but doleful image from the Rajput state of Bundi in which we, along with a princely voyeur behind the banana trees, can spy on a lady biding her time with her maid and a school of fish eager for their daily rations.

Prince and Princess Hunting Blackbuck - Art Institute of Chicago

(Image source)

Significance of Hunting

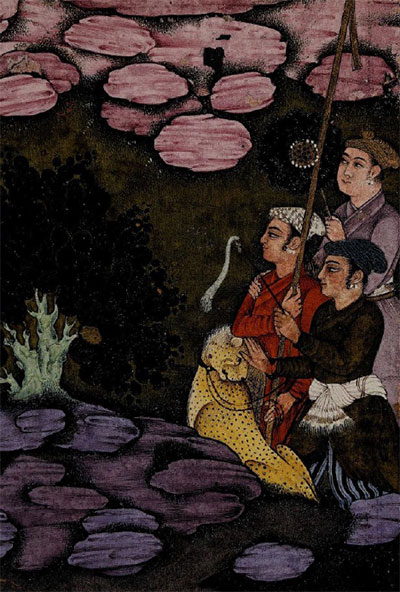

In Islamic miniature paintings, hunting scenes are often depicted with great attention to detail and artistic skill. These paintings are not only a representation of the hunt itself but also a symbol of the spiritual search for the divine. The animals, the landscapes, and the human figures all carry symbolic meanings that allude to the spiritual significance of the hunt.

Mughal, c. 1585 (central image); Rajasthan, Mate seventeenth/early eighteenth century

(border) Opaque watercolor cm Lucy Maud Buckingham Collection

(Image source)

In a splendid portrait of the Mughal prince Azam Shah, painted in the third quarter of the seventeenth century, the artist chose to represent him as a keen falconer. Sometimes an unexpected bonus during a hunt was a visit to a holy man who lived in the forest. One Shah Jahani picture in the collection, probably painted in Kashmir, portrays such a visit. These pictures were particularly popular with the Mughals, as the earthly hunt in Islamic cultures is a metaphor for the search for the divine.

While cattle depictions were not the primary focus in Mughal hunting paintings, they were occasionally included in the composition. Mughal hunting paintings were a popular genre of art during the 16th to 19th centuries and typically depicted royal hunts, with the emperor or nobles pursuing game on horseback with the help of falcons or other birds of prey.

Cattle depictions in these paintings were often secondary to the primary subjects of the hunt, which were usually wild animals such as tigers, deer, and boars. However, domesticated animals such as cows and buffaloes were sometimes included in the background or foreground of the composition, as they were commonly found in the rural landscape of Mughal India.

The depiction of cattle in Mughal hunting paintings was often used to enhance the realism and naturalism of the composition, providing a sense of context and scale. Cattle were also sometimes included as part of the narrative of the painting, such as in scenes where the hunting party was crossing a river or passing through a village.

(Image source)

(Image source - right)

Varying Proportions for different animals

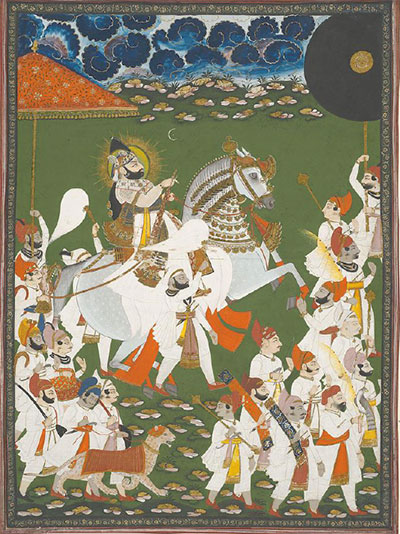

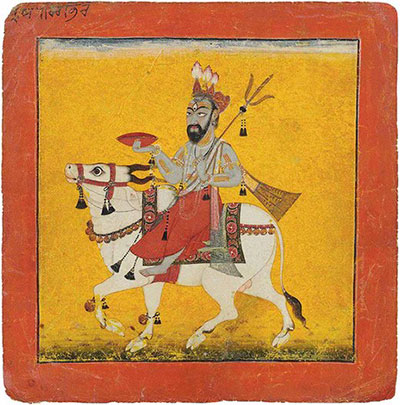

Animals were, of course, the principal mode of transportation for the rich and powerful. The elephant and the horse were the two favorites, as we see in two beautiful pictures. The earlier of the two, from the Padshahnama, an album prepared for Shah Jahan to record his imperial rule, is a detailed and acutely observed rendering of an imperial procession that conveys all the pomp and pageantry of such occasions. While the caparisoned elephant reveals the traditional confidence of Indian artists in representing the pachyderm, the more naturalistic depiction of the horse in Indian art is a contribution of the Mughals. In the Indian way of thinking, however, the horse bearing royalty was not just another animal to be observed and drawn accurately. It could not match the elephant for size in life, but in art its form could be manipulated to convey the majesty of the ruler. So in a magnificent Mewar picture, the horse’s splendidly embellished form reiterates the importance of his royal, and, indeed, divinized rider.

Maharana Bhim Singh Attributed to Ghasi lactive 1820/36) Rajasthan, Mewar, Udaipur Royal Atelier, Everett and Ann McNear Collection

(Image source)

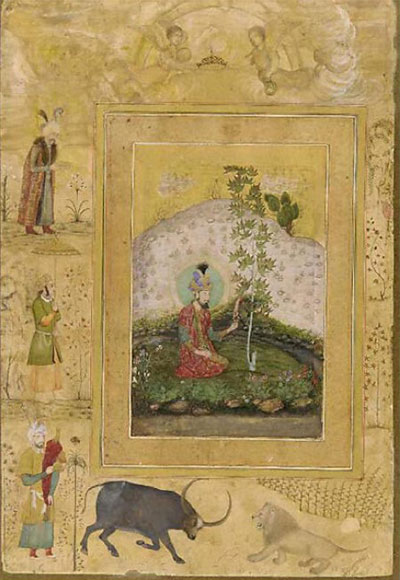

In some Mughal-era paintings, yogis from different sects, including Nath, Ramanandi, and Sannyasi, are depicted alongside cattle. These paintings typically showcase the yogis in a meditative or contemplative state, often surrounded by natural elements such as trees and animals. The depiction of yogis and cattle together in Mughal-era paintings also reflects the complex social and cultural milieu of the time. These paintings showcase the interaction and overlap between different religious traditions, and the ways in which spiritual practices were influenced by the natural world.

Bifolio from the Gulsham Album.

(Image source)

Cattle depictions were a common feature on the borders of Mughal miniature paintings. These borders were typically decorated with intricate designs and patterns, often featuring a variety of animals, birds, and plants.

The cattle depicted in the borders of Mughal miniature paintings were often stylized and abstract, with elongated bodies and curved horns. They were typically depicted in profile, facing to the left or right, and were often accompanied by other animals such as deer, birds, or monkeys.

Humayan Seated in a Landscape with a Plane Tree, Admiring a Turban Ornament: Page from the Late Shah Jahan Album

(Image source)

Mughal emperors and nobles were passionate about the natural world and often commissioned artists to document the flora and fauna they encountered. The resulting paintings are highly detailed and realistic, capturing the intricate patterns and colors of plants, birds, animals, and insects.

One of the most famous Mughal painters, Mansur, was renowned for his detailed studies of plants and animals, which he created for Emperor Jahangir’s botanical album. His paintings documented the flora and fauna of the Indian subcontinent with such precision and accuracy that they are still used as scientific illustrations today.

Ustad Mansur

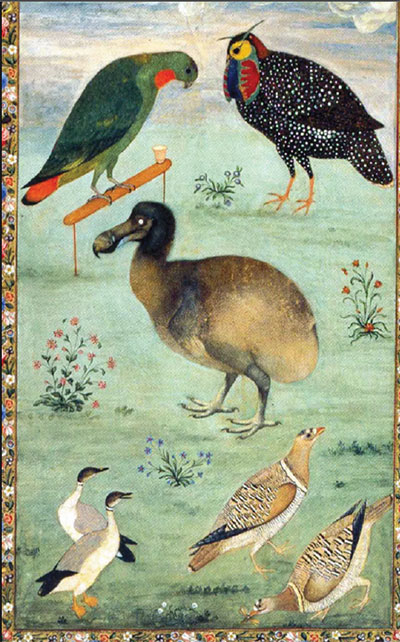

Ustad Mansur was a famous Mughal painter who lived during the reigns of Jahangir and Shah Jahan in the 17th century. He was known for his exceptional talent in painting animals, birds, and flowers, and his work was highly prized by the Mughal emperors and other members of the court.

The significance of Ustad Mansur’s paintings lies in their exceptional beauty and detail, as well as their importance in documenting the flora and fauna of India during the Mughal period. Mansur’s paintings were highly realistic and captured the unique qualities of each animal, bird, or flower he depicted. His paintings also provide valuable insights into the Mughal court’s fascination with nature and their efforts to understand and classify the natural world around them. His paintings were not just artistic masterpieces but also served as important records of the biodiversity of the Mughal era. The accuracy of his paintings helped naturalists and scientists in identifying and classifying the flora and fauna of the time.

A painting depicting the dodo ascribed to Ustad Mansur dated to the period 1628-33. This is one of the few coloured images of the dodo made from a living specimen.

(Image source)

Many of Ustad Mansur’s paintings feature rare and exotic species, which were not known to Europeans at the time. For example, his painting of a dodo, which is now extinct, is one of the earliest depictions of the bird in the world.

(Image source)

(Image source - right)

(Image source)

(Image source - right)

Rajput School of Paintings

Rajput paintings of the Mughal era were a distinct artistic style that emerged in the royal courts of the Rajputana region (present-day Rajasthan) during the 16th and 17th centuries. These paintings were influenced by the Mughal art style, but also incorporated local Rajput elements and iconography.

Rajput paintings of this era often depicted scenes from Hindu mythology and epics, such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata, as well as portraits of Rajput rulers and nobles. The paintings were typically characterized by their vibrant colors, intricate details, and the use of gold and silver to embellish the artwork.

Overall, the Rajput paintings of the Mughal era represent a unique fusion of local traditions and Mughal influences, and are an important part of India’s rich artistic and cultural heritage.

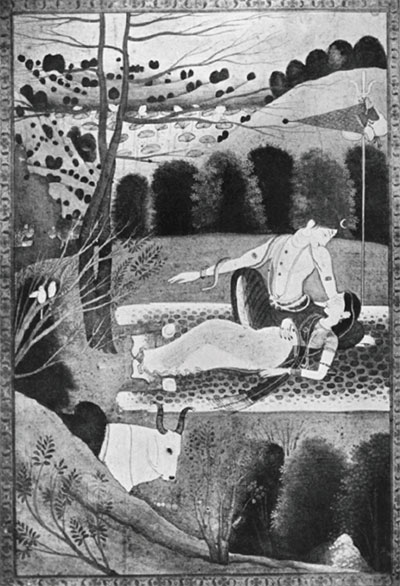

Siva and Parvati. Pahari. Ascribed to Mola Ram of Gahrwal (D. 1833). Author's Collection

(Image source)

Siva and Parvati

Early nineteenth century. Rajput, Pakari, attributed to Mola Ram. A moonlit night in the hills, Siva watching over Parvati sleeping. Siva’s trisul, drum, gourd and banner on the right, the bull Nandi on the left; a lotus lake and low wooded hills in the distance. The clear night effect is very well suggested; the figure of the Great God is drawn with much tenderness. The trees are somewhat artificial, the figure of Parvati a little stiff, the fingers unnaturally pointed; these may be regarded as late features in a work otherwise well designed, and fascinating by its romantic, but not sentimental, tenderness.

Krishna and Cows

The geographical relevance of Krishna’s association with cattle in paintings is rooted in the mythology and traditions of the region of Vrindavan, located in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. According to Hindu mythology, Vrindavan is the place where Krishna spent much of his childhood as a cowherd. The region is known for its lush pastures, where cows and other animals graze, and it is believed that Krishna spent his days herding cattle and playing with his friends in the fields.

(Image source)

(Image source - right)

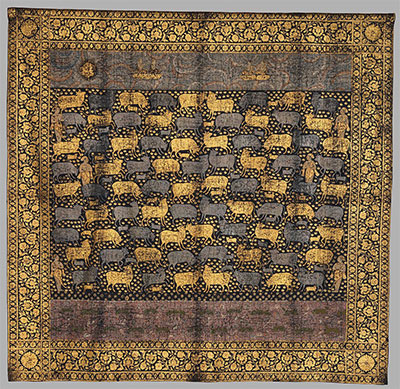

Large painted cloths (Pichhwais) were made to hang behind the main image in a temple. This textile was produced for the Festival of Cows (Gopashtami), which occurs in late autumn to celebrate Krishna’s elevation from a herder of calves to a cowherd. Note the range of cows and frolicking calves that populate the flower-strewn field. The indigo ground and extensive use of gold and silver are typical of Pichhwais that was made for a community of Sri Nathji(Shrinathji is a form of Krishna, manifested as a seven-year-old child) devotees who moved to the Deccan during this period.

At these pilgrimage centers, large painted cloths (Pichhwais) were hung behind the primary stone images of Shri Nathji in accordance with the festival calendar (2003.177). This textile was produced for the Festival of Cows (Gopashtami) which takes place in the late autumn to celebrate Krishna’s elevation from a herder of calves to a cowherd. Note the range of cows and frolicking calves that populate the flower-strewn field. The indigo ground and extensive use of gold and silver are typical of Pichhwais which were made for a community of Shri Nathji devotees who moved to the Deccan during this period. Emphasized is the idea of natural abundance central to the Shri Nathji tradition: the word shri actually carries the meaning of prosperity.

Pichhwai for the Festival of Cows India, Deccan, Aurangabad late 18th century

(Image source)

Pahari School Paintings

Pahari painting (literally meaning a painting from the mountainous regions: Pahar means a mountain in Hindi) is an umbrella term used for a form of Indian painting, done mostly in miniature forms, originating from Himalayan hill kingdoms of North India, during 17th-19th century Pahari painting grew out of the Mughal painting, though this was patronized mostly by the Rajput kings who ruled many parts of the region, and gave birth to a new idiom in Indian painting.

At the moment depicted in this painting, she has succeeded in beheading the buffalo demon and shooting arrows into his true form that climbs from its neck. Artists in the foothills of the western Himalayas, where this work was made, depicted Durga’s mount as a tiger—lions and tigers had synonymous meaning throughout India as emblems of shakti, or divine creative energy.

Shiva and Nandi

In Pahari paintings, Nandi and Shiva are often depicted together as they are considered inseparable in Hindu mythology. Nandi is the divine vehicle and gatekeeper of Lord Shiva, while Shiva is the Hindu god of destruction and one of the three main deities in the Hindu pantheon.

The depictions of Nandi and Shiva in Pahari paintings are often used to convey the message of devotion and surrender to a higher power. These paintings also showcase the beauty and intricacy of Indian miniature painting, as well as the rich cultural and religious heritage of the Pahari region.

Ragmala Paintings

The Ragmala paintings are a set of Indian miniature paintings that depict various musical modes (ragas) of Indian classical music, along with accompanying poetry. These paintings often feature depictions of Hindu gods and goddesses, as well as scenes from mythology and literature.

A narrative genre that is wholly Indian and that was extremely popular with patrons of Indian painting from the seventeenth century onward is known as Ragamala, literally, “garland of melody.” Ragamala paintings illustrate six basic musical modes known as Raga and thirty or more derivatives designated as Ragini. A Raga is a male while Ragini is a female. Poets composed short verses, often included above the pictures, about these modes. These verses provide a word picture of a romantic situation or a devotional sentiment that was given visual expressions by the artist. Often animals are included in these paintings as companions of the personified Raga or Ragini, as an empathetic audience, or as symbols, visual metaphors, or allegories. The three examples selected here are representations of the Raginis known as Kakubha, Todi, and Bangal.

Lord Shiva - Bhairava Raga. Pahari, Nurpur, c. 1690. Opaque pigments heightened with gold on paper, Shiva holding an alms bowl and a trident seated on the bull Nandi, within black rules and red borders, inscription in black Takri script to the upper left corner 8 1⁄4 in. (21 cm.) square.

(Image source)

Ragamala paintings representing the essence or mood of musical composition were another popular genre that often also had devotional significance. In a work that gives pictorial form to the music of the Vasant Ragini, a central dancing nobleman plays the role of Krishna in celebration of the coming of spring (1999.148). He holds a vina (stringed instrument) over his shoulder and lifts up a pot out of which a flowering plant emerges. His skirt of peacock feathers makes his association with Krishna clear, while the surrounding female musicians recall Krishna’s Raslila dance with the Gopis (cowherdesses).