Design Resource

Animal Depiction in Indian Art throughout History

The representation of cattle and its evolution over time

by

The Mauryan Empire existed from approximately 322 BCE to 185 BCE and was known for its political and cultural achievements. The art of the Mauryan Empire was influenced by Buddhist and Jain teachings, which emphasized non-violence and compassion towards all living beings. As a result, the animal depictions in Mauryan art were largely symbolic and but naturalistic. For example, the famous Lion Capital of Ashoka, which is now the emblem of modern India, features four lions standing back to back, each with a different expression. This depiction of the lion symbolises strength, power, and the benevolent rule of the Mauryan Empire.

Some of the most notable examples of Mauryan art include:

• Pillars:

The Ashoka Pillars are one of the most recognizable Mauryan artefacts. They are tall columns made of polished sandstone and feature elaborate carvings depicting animals, plants, and various other motifs.

• Stupas:

Stupas are Buddhist structures that are used to enshrine relics or commemorate important events. The Great Stupa at Sanchi is one of the most famous Mauryan stupas. It features intricate carvings and sculptures that depict scenes from the life of Buddha.

• Stone sculptures:

The Mauryan era is also known for its stone sculptures, which are noted for their realism and attention to detail. Some of the most famous examples include the Yakshi figures at the Sanchi Stupa and the Didarganj Yakshi.

• Coins:

The Mauryan dynasty was one of the first Indian dynasties to issue coins as a means of exchange. Made of silver, copper, and gold, these coins often featured images of animals, plants, and other symbols that were important to the Mauryan culture. The coins were also inscribed with various legends in Brahmi script, which provide important historical and linguistic information.

Overall, Mauryan art and artefacts are known for their intricate detailing, realistic depiction of human and animal forms, and their unique blend of indigenous and Hellenistic influences.

The Lion Capital

The Lion Capital discovered more than a hundred years ago at Sarnath, near Varanasi, is generally referred to as Sarnath Lion Capital. This is one of the finest examples of sculpture from the Mauryan period.

The pillar capitals are divided into three parts: the lotiform bell at the bottom; the abacus, and the animal sculpture on top. The lotiform bell-shaped bases of the capitals—named for their resemblance to an inverted lotus—are composed of long petal-like units enclosing a second row of smaller, more angular petals. The abacus is a band that goes around a capital and is decorated with floral and animal motifs in relief: flamed palmettes with multiple calyxes, rosettes and honeysuckles interspersed with figures of the lion, bull, horse and elephant. The animal sculptures, noted for their neat, restrained style and precise anatomical detail, are located at the top of the Ashokan capitals.

Capital of inscribed Asoka Pillar at Sarnath. (A. S. photo)

(Image source)

These animals are believed to have symbolic significance and represent various aspects of Ashoka’s reign and beliefs. The bull, for example, is a symbol of strength and power and may represent the might of the Maurya Empire. The lion, on the other hand, is a symbol of royalty and courage and may represent Ashoka’s authority as a king. The elephant, with its association with wisdom and longevity, may symbolize Ashoka’s commitment to promoting social welfare and justice. Finally, the horse, with its association with speed and agility, may symbolize Ashoka’s commitment to maintaining an efficient and well-organized administration.

Ashokan lion capital from the Deer Park at Sarnath.

(Image source)

The Dharma Chakra

The Dharma Chakra (also spelt Dhamma Chakra) is a symbol that represents the teachings of Buddha, and it is often used in various forms of Buddhist art and architecture. In addition to the Indian national emblem, the Dharma Chakra is also commonly used in statues and other artwork across various countries in Asia.

In addition to the Lion Capital, there are many examples of statues and artwork that feature the Dharma Chakra and various animals in Buddhist traditions. For instance, the Great Stupa of Sanchi in India features a depiction of the Dharma Chakra, as well as various animals such as lions and elephants. Similarly, the Borobudur temple in Indonesia also features carvings of animals such as elephants and lions, as well as depictions of the Dharma Chakra.

One of the notable features of Mauryan art is the depiction of animals alongside the dhamma chakra or the wheel of law, which is a symbol associated with Buddhism and Jainism. These animals include lions, elephants, bulls, horses, and deer, which are often depicted in pairs or groups around the dhamma chakra. These animal depictions were often highly stylized and ornate, with intricate details and symbolic meanings.

The inclusion of animal depictions alongside the dhamma chakra highlights the importance of nature and the environment in ancient Indian culture and religion. It also suggests a deep reverence for animals and their symbolic and spiritual significance in Mauryan society.

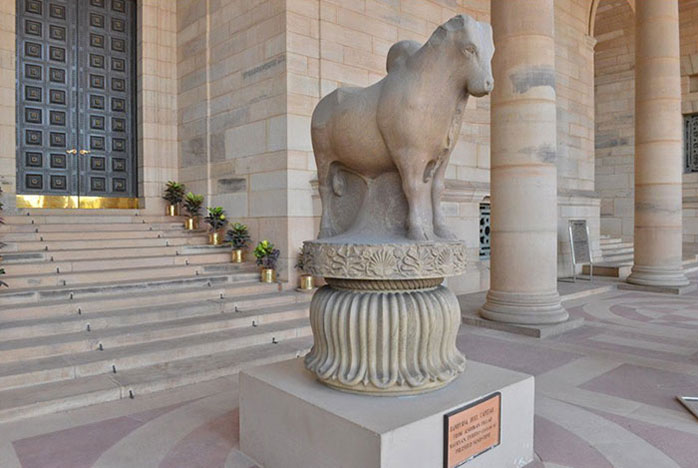

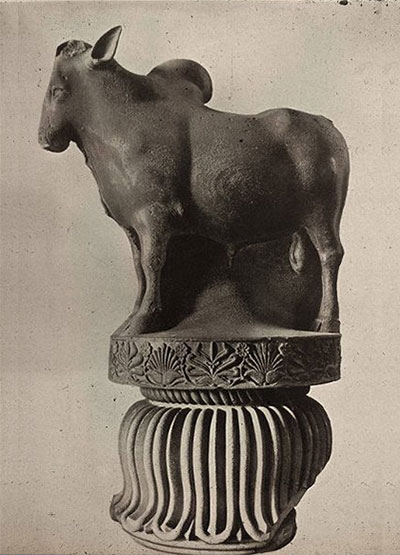

Rampurva Bull

Rashtrapati Bhawan holds another one of its pillars, the beautiful Rampurva Bull, the Ashokan Pillar’s sandstone capital from the third century B.C. It receives its name from the place where it was discovered, Rampurva in Bihar. The Rampurva Bull stands on a pedestal between the Rashtrapati Bhavan’s central pillars at the Forecourt entrance.

The Rampurva Bull is known for its carefully sculpted figure, which depicts soft skin, sensitive nose, attentive ears, and muscular legs. It is a mixture of Indian and Persian elements.

Rampurva Bull, Rashtrapati Bhavan.

(Image source)

The Ashokan pillars at this location are thought to commemorate Buddha’s renunciation. Ashoka installed two pillars (a lion and another bull) here to commemorate this event in Buddha’s life. Some locals believe the lion-headed pillar represented Lord Buddha, while the bull-headed pillar represented his charioteer companion Chandak, whom he had asked to return to the palace with his discarded royal garments.

Ashokan pillar capital with bull, Maurya dynasty, India, ca. 3rd century B.C.

(Image source)

The Stupas

The Sanchi Stupa Buddhist complex in the town of Sanchi (State of Madhya Pradesh, India). The Great Stupa is one of the oldest stone structures in India and was originally commissioned by the emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE. Top Right: Carved decoration of the Northern gateway (torana) to the Great Stupa of Sanchi. Bottom: Close up of one of the panels of the southern torana of the Great Stupa showing King Ashoka visiting Ramagrama to take relics of the Buddha from the Nagas.

All the elements are covered with relief sculptures depicting the events of the Buddha’s life, Jataka stories (about the Buddha’s previous lives), scenes of early Buddhism, and auspicious symbols.

(Image source)

(Image source - right)

(Image source)

(Image source - right)

(Image source)

(Image source - right)

Cattle were also depicted in more utilitarian contexts, such as in scenes of farmers ploughing fields or using bullock carts to transport goods. These depictions were more focused on the practical aspects of cattle, rather than their symbolic or aesthetic qualities.

In conclusion, while cattle were not given the same level of artistic attention as elephants and horses in Mauryan art, they played a vital role in the Mauryan economy and society, and their depiction in art reflected their practical and utilitarian role in daily life.

Post Mauryan Influence

Apollodotus I was a Greek king who ruled in the northwestern Indian subcontinent during the 2nd century BCE. The Mauryan Empire was a powerful Indian empire that existed during the 3rd century BCE.

The exact significance of the animals depicted on the coins is unclear. The sacred elephant may be the symbol of the city of Taxila, or possibly the symbol of the white elephant that reputedly entered the womb of the mother of the Buddha, Queen Maya, in a dream, which would make it a symbol of Buddhism, one of the main religions of the Indo-Greek territories.

Similarly, the sacred bull on the reverse may be a symbol of a city (Pushkhalavati), or a depiction of Shiva, making it a symbol of Hinduism, the other major religion at that time.

Nandipada

The Nandipada (“foot of Nandi”) is an ancient Indian symbol, also called a taurine symbol, representing a bull’s hoof or the mark left by the foot of a bull in the ground. The Nandipada and the zebu bull are generally associated with Nandi, Shiva‘s humped bull in Hinduism.[1] The Nandipada symbol also happens to be similar to the Brahmi letter “ma”.

The Nandipada appears on numerous ancient Indian coins, such as coins from Taxila dating to the 2nd century BCE. The symbol also appears on the zebu bull on the reverse if often shown with a Nandipada taurine mark on its hump on the less worn coins, which reinforces the role of the animal as a symbol, religious or geographic, rather than just the depiction of an animal for decorative purposes. The same association was made later on coins of Zeionises or Vima Kadphises.

Indian coin of Apollodotus I, with a nandipada taurine symbol on the hump of the zebu bull.

(Image source)