Static Visual Narratives or SVNs are those visuals that do not move in time (per say). These visuals are represented on mediums such as paper, wood, stone etc. that render the visuals motionless. It is broadly owing to these criteria that we call such visuals ‘static’. By ‘static’ we refer to the inability of the visual to move or change within the medium in time. Thus, a narrative that is visual in nature and occurs on a static (stationary, motionless) medium such as paper, wall, an object, stone etc. is called a Static Visual Narrative [SVN]. The image is fixed by means of etching, drawing, painting, printing, sculpting onto the surface. It is an illusion created to evoke the experience of the story being told. By this token narrative art, pictorial narratives, narrative sculpture, picture stories, comics, info-graphics on paper, picture books etc. are in core SVNs.

Definition of SVN:

We define the Static Visual Narrative as a notion that comprises of a set of physical markers on an immobile medium, which presents the content (story) through a mechanism of temporal and spatial visual representation.

Characteristic Features of the SVN:

1. The SVN executed on a medium occupies surface area. For example an illustrated comic book runs over many pages, or a mural painting may cover an entire wall. The viewer has to unravel the story by exploring the surface area covered by the visual. Thus the story unfolds across space.

2. In the case of the SVN the image is fixed on the surface of the medium. That is to say it remains materially unchanging. Le Poidevin defines ‘A static image (as) one that represents by virtue of properties which remain largely unchanged throughout its existence’ (Le Poidevin, 1997:175). For example once a story has been painted or printed on a piece of paper it does not undergo much change except for maybe fading with time.

3. SVNs bank on the spectator’s prior knowledge of the narrative. Only then can the viewer fully enjoy reading the SVN, as the intent of the visual narrative is to engage the spectator within it. ‘Perception’ and ‘Memory’ play an important role in this respect. The viewer has to recall the event in story and match it to the event portrayed in the SVN. The spectator already knows what has happened (the past) and what is to come (the future) but engages in unravelling the SVN as the designer has presented.

4. The visual is fixed but the viewer or the viewer’s eye is mobile. The SVN is viewed by a moving spectator, who finds connections between juxtaposed scenes that communicate a meaning. The spectator turns the pages or stands back in front of a sculptural panel; it is the eye that moves and explores the visual. Souriau illustrates this point by citing the example of viewing a statue ‘ His (the viewer’s) movement around the statue brings to view, as it were, melodically, the various profiles, the different projections, shadow, and light; thus the most complete appreciation of the aesthetic complexity of the work is gained only be the moving spectator’ (Souriau, 1949:295).

5. The viewer of the SVN decides the speed at which to view the image. The SVN by the fact that it is fixed permits the spectator to travel around the visual at leisure, allowing for pauses at any given point for as long as is desired or quickly skimming through the visual.

6. In an SVN the order of viewing is not determined; the spectator decides the order in which to view the SVN. A choice can be made as to where to begin viewing the SVN. Having known the story, one can decide to begin viewing the story from any given point in the narrative and go backwards or forwards accordingly. One can even begin with the end and view the whole narrative in a flashback kind of manner. In other words the SVN can be read from beginning to end, vice versa or begin in media res as per the preference of the viewer.

7. Imagination plays a big role in the appreciation of the SVN. The SVN heavily banks on the imagination of the spectator to make use of the visual cues and build the story.

8. The viewer is in full control of the contemplation time or as Goswamy refers to it ‘the ruminative viewing’ i.e. time taken to carefully regard a work of art (Goswamy, 1998). The spectator is in control of the time taken for viewing the SVN.

9. Perception of movement in the SVN results from the active participation of the spectator. The viewer has to look at the SVN recall the story and engage in the process of narration. The SVN makes great demands on the viewer’s ‘Imagination’. The beauty of the SVN is that it only provides cues to the story in the form of visuals. It is up to the viewer to use those cues as a base to build the narrative.

Professor Hernshaw refers to this as ‘temporal integration’, the bundling together in one extended stretch of time of memories and expectations (as quoted by E.H. Gombrich, 1964).

An excellent example of a SVN is a panel from the Gates of Paradise that represents the story of Adam and Eve.

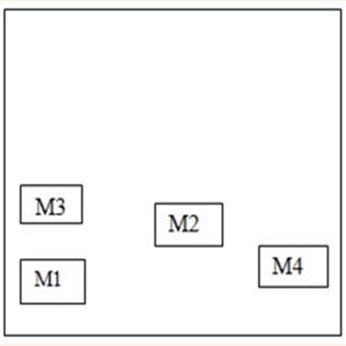

Shown in the SVN (Fig.01), at the left bottom corner, we see God in the act of creating Adam (moment 1 – M1). Next, in the centre unfolds the creation of Eve (moment 2 – M2). Show in low relief towards the left is Adam and Eve being tempted by the Devil in the form of a snake (moment 3 – M3). Finally on the right side, we see the couple being thrown out of the Garden of Eden by the angels on the orders of God (moment 4 – M4). Broadly speaking the narrative flows from left to right, but the viewer can read the narrative from any point moving back and forth in the intrinsic story-time.

Fig.1: SVN representing the story of Adam and Eve, Gates of Paradise*

* Panel from Lorenzo Ghiberti’s “Gates of Paradise”, Florence Baptistery, Italy.

Image Source –Web Gallery of Art.