Introduction:

Corporate Identity Systems work on the premise that there is the need for a corporation to be perceived as being different from the ordinary, especially in a business climate that is increasingly being besieged by pressures of several kinds - political, social, economic. What does the corporation then do to fight its way out of an impending or an anticipated situation of facelessness?

We will exemplify this process with a recent hands-on experience that is known to have set a few precedents in India through its design initiatives. This is the Vision 2000 programme under which India's largest as well as her only Fortune 500 company, the Indian Oil Corporation (IOC), had set itself on a course of revamping its corporate image three and a half years ago. Part of the outcome is now available in the form of a recently inaugurated retail petroleum outlet near the international airport of Sahara in Mumbai. The outlet bears testimony to an arduous, and needless to say, comprehensive designing programme backed up by an equally stringent implementation process. Also arguably the first of its kind in India, the programme was systematically initiated in the fall of 1994.

• The objectives for IOC

• The design idioms for Vision 2000

• The Design Solutions

• The Key Design Features

• Conclusion

• The Designers

The objectives for IOC:

Any design solution as part of a corporate image-building exercise needs to be a construction of the statement of the company's attitudes and goals. Followed by the backing of a clear-cut design idiom. The imperatives for a change in IOC's corporate image were rooted in several factors. In a survey undertaken by the designer commissioned by IOC to undertake its image-building programme, it would appear that on an everyday basis, neither the company's image nor its performance left any indelible imprint in the minds of its consumers. A finding that applied equally well to all the other oil companies in India as well. In the event, the only way to distinguish one oil company from the other seemed to be the colour-bands running across their pump station facias - red in the case of IOC, yellow for BPCL, blue for HP and orange for IBP. And even there, the customers found it difficult to remember which colour represented which company. It was this 'impersonality' which had lent to the company's image an utterly unexciting impression, and one that now required immediate addressing.

The design idioms for Vision 2000:

As mentioned already, one of the first steps towards any image-building exercise is also usually marked by the adoption of a clearly defined set of design idioms. Which is why a similar course of action was expected to set the way for IOC to accomplish a clearer identity aimed at transforming the corporation's impersonal image. In the designer's opinion, this could only happen by evolving a 'design style' that was "manifoldly distinct from the prevalent ones," apart from projecting IOC as a 'consumer- friendly' company. This image-building exercise was now going to be undertaken systematically through a design programme designated by the designer as 'Vision 2000'. Under this, projects would either be an outcome of a redesigned effort, as in the case of all existing retail IOC outlets across the country. Or designed from scratch in the case of a few select retail outlets yet to be constructed. And which would sport an entirely new look. As in the case of the project under discussion here.

One of the two design idioms considered appropriate for this programme was 'comprehensive designing' that would consist of designing an entire range of artifacts right from buildings to products to packaging to publicity material, rather than just a few items here and there chosen in a piecemeal manner for designing. All this, of course, with a view to creating a composite mental picture of the company in the minds of its consumers. Included under comprehensive designing process would be an entire gamut of artifacts, such as the architecture of the sales building of the retail outlets, the canopy to cover the oil-pumps, signage poles to guide the traffic around, the uniform to be worn by attendants at the pump station, the size and positioning of the billboards, and such.

The other major design idiom adopted under IOC's Vision 2000, and which is seldom undertaken by India's industry, was the concept of 'proprietariness'. It is an undertaking through which materials and processes are developed exclusively for the company's use. In the event, it would give IOC a major competitive edge to its revamped corporate identity by pre-empting the company's design initiatives from getting undercut through cheap imitations.

The Design Solutions:

There were three design solutions offered as alternatives to IOC. Each one reflecting a certain style of designing, and each style in turn, representing a certain sense of purpose distinctly associated with that particular style. Of these three solutions - traditional, modern and post-Modern - presented in the form of models to the company for them to be able to visualize the projected outcomes, the one selected by IOC for implementation was the post-Modern one. In the words of the designer, the post-Modern design was based on "an open, dynamic form in order to go along with the futuristic aspirations of the company."

It is widely known that post-Modern design represents an attitude towards precision and purpose, but not in a driven industrial sort of way. Instead, it is an idiom of design that admits outside sensibilities with less reservations, this by itself connoting an attitude towards change. With its roots in the post-seventies' movement called Memphis, post-Modern design had sign posted, through its protagonists such as Ettore Sottsass, Peter Shire, Natalie Pasquire and others, a note of protest against the orthodoxy of the prevailing design culture of the rectilinear that had swept the Western world since the twenties. Which is why some of the key design features of Vision 2000 display a move towards the curvilinear.

Adopting a post-Modern style for IOC's revamped corporate image was going to send out a signal of unorthodoxy in an otherwise undifferentiated environment of staticness that had come to mark the corporate-industrial scene in India. IOC now desired itself to be projected as a 'futuristic' corporation "poised at the cutting edge of technology, and up-to-date in appearance" apart from being a 'friendly' corporation.

The Key Design Features:

Decidedly, one of the elements in the overall design scheme that was going to impart IOC's future retail outlets with a sense of distinctiveness, was going to be its colour identity. In its completed form at the new retail outlet near Mumbai's international airport at Sahara, it appears quite strikingly as a rainbow-coloured band that runs visibly along the entire length of the retail outlet's facia. Needless to say, the rainbow band is of a proprietary nature, made in PVC and reproduced either through digital printing or through screen printing. Then, there is the house colour chosen by the designer especially for Vision 2000. It is a proprietary 'IOC Beige.' Further, the colour combination of white letters on a red background developed specifically for IOC, has been set aside for use on its signage’s.

It is widely known that post-Modern design represents an attitude towards precision and purpose, but not in a driven industrial sort of way. Instead, it is an idiom of design that admits outside sensibilities with less reservations, this by itself connoting an attitude towards change. With its roots in the post-seventies' movement called Memphis, post-Modern design had sign posted, through its protagonists such as Ettore Sottsass, Peter Shire, Natalie Pasquire and others, a note of protest against the orthodoxy of the prevailing design culture of the rectilinear that had swept the Western world since the twenties. Which is why some of the key design features of Vision 2000 display a move towards the curvilinear.

Adopting a post-Modern style for IOC's revamped corporate image was going to send out a signal of unorthodoxy in an otherwise undifferentiated environment of staticness that had come to mark the corporate-industrial scene in India. IOC now desired itself to be projected as a 'futuristic' corporation "poised at the cutting edge of technology, and up-to-date in appearance" apart from being a 'friendly' corporation.

The Key Design Features:

Decidedly, one of the elements in the overall design scheme that was going to impart IOC's future retail outlets with a sense of distinctiveness, was going to be its colour identity. In its completed form at the new retail outlet near Mumbai's international airport at Sahara, it appears quite strikingly as a rainbow-coloured band that runs visibly along the entire length of the retail outlet's facia. Needless to say, the rainbow band is of a proprietary nature, made in PVC and reproduced either through digital printing or through screen printing. Then, there is the house colour chosen by the designer especially for Vision 2000. It is a proprietary 'IOC Beige.' Further, the colour combination of white letters on a red background developed specifically for IOC, has been set aside for use on its signage’s.

Some of the other features that are the result of a dedicated proprietary development for the corporate identity exercise are:

• the concept of a convenience store on the premise of a retail outlet and which combines the conveniences of emergency shopping and snacking with the act of filling up gas;

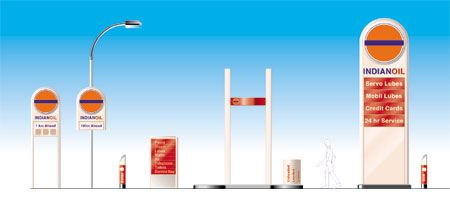

• a range of signage’s which are of a distinct shape and colour-combination and which include the main sign poles indicating all facilities available at the outlet, as well as directional sign - poles and signage’s for the pump island and the convenience shop;

• the curvilinear dumbbell-shaped pump islands to help the vehicles maneuver themselves with ease, as well as to create space for the pump attendants to stand and attend to the vehicles;

the facia band in steps, as a feature along the top of the canopy as well as on the sales and service building; and

• the positioning of the oil-pumps in two separate spaces of the retail outlet - one of them to provide easy access to two and three wheelers, the other to four wheelers.

This segregation is expected to promote better space and functional management of the arriving vehicles in terms of the customized attention that can now be accorded to the varying needs of two and three wheelers vs. those of four wheelers.

Conclusion:

It is just as well that a Fortune 500 company should have taken the plunge towards such a potentially massive exercise in comprehensive and proprietary designing and set the pace for the others to follow. What holds a measure of promise through this particular design endeavor, are the clues that are embedded in the corporation's initiative towards indigenous designing. Compared to the usual tendency in the industrial design history of the Indian industry to plump in for already available designs, even if such designs have been worked out to suit the needs of companies located elsewhere, and quite usually of those located abroad.

It has to be said in a measure of fairness to IOC, that it was the top echelon of its management that had opened up the doors for indigenous designing. The strategic positioning that it had created for the designer right from the point in time at which he was commissioned into the launch of the Vision 2000 programme, could have a strong message for other corporations in India especially the ones that could be in an urgent need for a corporate image-building exercise. The fact that such strategic positioning had enabled the designer access to the topmost levels of the management compares well with the way companies like IBM or Mobil had gone about their own such exercise in the sixties. The relative face of coherence displayed amongst IOC's top management, especially with respect to the critical matter of freezing their design concept in order to move on with its implementation, had all the hallmarks of a company getting ready for marketisation.

If IOC were to conform to a strict implementation-regime of its Vision 2000 programme, in accordance with the guidelines laid out in its manual by the designer for its pan-India application (across an estimated 7000 retail outlets to be redesigned by the year 2000). And, if there were to be strict adherence to material and process control, then IOC's post-Modernist 'rainbow band' could yet turn out to be her lucky mascot.

The Designers:

• a range of signage’s which are of a distinct shape and colour-combination and which include the main sign poles indicating all facilities available at the outlet, as well as directional sign - poles and signage’s for the pump island and the convenience shop;

• the curvilinear dumbbell-shaped pump islands to help the vehicles maneuver themselves with ease, as well as to create space for the pump attendants to stand and attend to the vehicles;

the facia band in steps, as a feature along the top of the canopy as well as on the sales and service building; and

• the positioning of the oil-pumps in two separate spaces of the retail outlet - one of them to provide easy access to two and three wheelers, the other to four wheelers.

This segregation is expected to promote better space and functional management of the arriving vehicles in terms of the customized attention that can now be accorded to the varying needs of two and three wheelers vs. those of four wheelers.

Conclusion:

It is just as well that a Fortune 500 company should have taken the plunge towards such a potentially massive exercise in comprehensive and proprietary designing and set the pace for the others to follow. What holds a measure of promise through this particular design endeavor, are the clues that are embedded in the corporation's initiative towards indigenous designing. Compared to the usual tendency in the industrial design history of the Indian industry to plump in for already available designs, even if such designs have been worked out to suit the needs of companies located elsewhere, and quite usually of those located abroad.

It has to be said in a measure of fairness to IOC, that it was the top echelon of its management that had opened up the doors for indigenous designing. The strategic positioning that it had created for the designer right from the point in time at which he was commissioned into the launch of the Vision 2000 programme, could have a strong message for other corporations in India especially the ones that could be in an urgent need for a corporate image-building exercise. The fact that such strategic positioning had enabled the designer access to the topmost levels of the management compares well with the way companies like IBM or Mobil had gone about their own such exercise in the sixties. The relative face of coherence displayed amongst IOC's top management, especially with respect to the critical matter of freezing their design concept in order to move on with its implementation, had all the hallmarks of a company getting ready for marketisation.

If IOC were to conform to a strict implementation-regime of its Vision 2000 programme, in accordance with the guidelines laid out in its manual by the designer for its pan-India application (across an estimated 7000 retail outlets to be redesigned by the year 2000). And, if there were to be strict adherence to material and process control, then IOC's post-Modernist 'rainbow band' could yet turn out to be her lucky mascot.

The Designers:

The principal designer for Vision 2000 has been Professor Ravi Poovaiah, a mechanical engineer from IIT, Madras and trained in Industrial Design from the Industrial Design Centre (IDC), IIT, Bombay, and Communications Design from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), USA respectively.

What is interesting here is the involvement of other industrial designers in informing the production aspects of the design features for the retail outlet. For one, there was Professor Sudhakar Nadkarni, Poovaiah's teacher and ex-colleague at the Industrial Design Centre (IDC), IIT, Bombay where Poovaiah functions as a senior member of faculty. Professor Nadkarni remained an essential part of the core design team through the entire course of the outlet's implementation.

But more interestingly has been the involvement of Kishore Babu from Bangalore, and Satish Raut from Bombay and both industrial designers, who were instrumental in the productionising of the canopy and the sign-poles respectively. There were yet others. For example, industrial designers such as Sanjay Jain and Kasturi Rangan of Wipro, whose lighting design developed for Vision 2000, although not adopted on this occasion, has become a classic design study for Wipro itself.

What is interesting here is the involvement of other industrial designers in informing the production aspects of the design features for the retail outlet. For one, there was Professor Sudhakar Nadkarni, Poovaiah's teacher and ex-colleague at the Industrial Design Centre (IDC), IIT, Bombay where Poovaiah functions as a senior member of faculty. Professor Nadkarni remained an essential part of the core design team through the entire course of the outlet's implementation.

But more interestingly has been the involvement of Kishore Babu from Bangalore, and Satish Raut from Bombay and both industrial designers, who were instrumental in the productionising of the canopy and the sign-poles respectively. There were yet others. For example, industrial designers such as Sanjay Jain and Kasturi Rangan of Wipro, whose lighting design developed for Vision 2000, although not adopted on this occasion, has become a classic design study for Wipro itself.