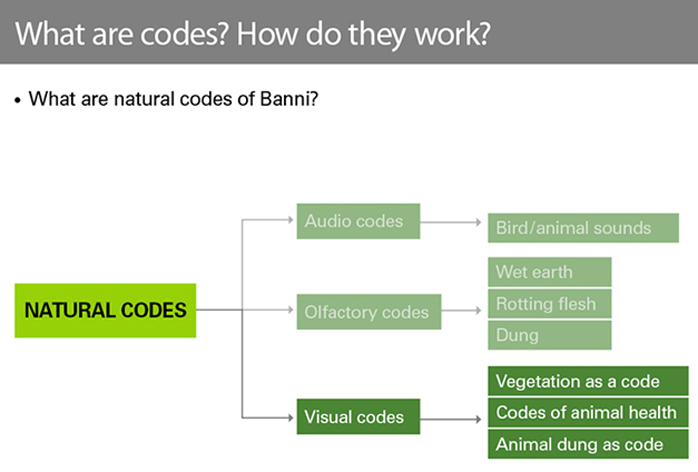

Natural codes of Banni grasslandS:

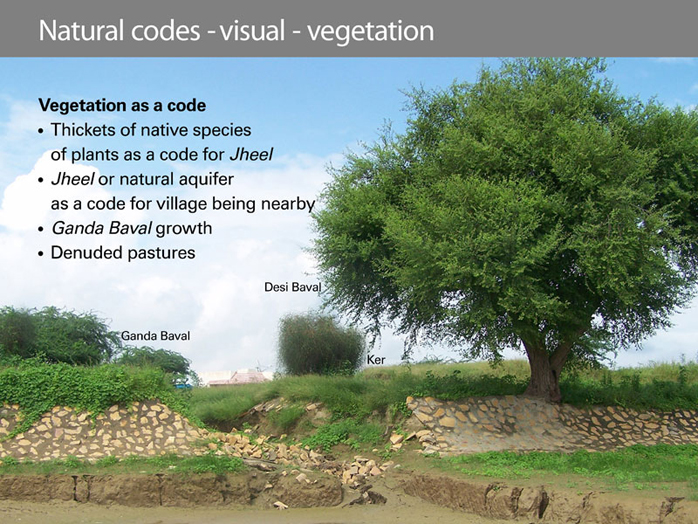

Vegetation as a code (See Fig. 2).

One cannot live in Banni without knowing its ecology. Villages in Banni may seem randomly placed, but they actually follow a pattern. If one looses way around Banni, one can squint and look towards the horizon in all the directions to find a thicket of trees belonging to native species like Mango, Desi Bawal, Bordi, and Ker. These trees grow only in regions with little salinity ingression and indicate presence of fresh drinking water sources. Such natural aquifers are locally called Jheel. A thicket of indigenous trees is a natural code for presence of a Jheel thereby a village nearby.

Dense Prosopis growth is an indication of grassland with excessive saline ingression. In Banni’s context it is a code for a degraded pasture. When these Gando Baval trees, will be replaced by native species like Mango, Desi Baval or Babool, Bordi and Ker it is an indication of a recuperating or a healthy pasture.

A pasture land infested with Gando Baval, is not suitable for cows (cows die as they fail to digest Gando Bawal pods) but buffalos feed on it. Thus pasture pockets full of Gando Baval or Prosopis Juliflora is a code that one is likely to find buffalos but unlikely to find cows here.

Camels feed on salty grasses of Banni called Lano. Pastures full of Lano, a code that one is likely to find camels here. These habitat codes and preferred pasture codes were especially useful back in the pre-cell phone days. Back then, when livestock animals were lost, Maldharis would look for codes like this to locate their animal.

A denuded pasture is a code that sheep and goat have been grazing here. When sheep and goat graze, they eat away roots of grasses and shrubs. A long time is needed for such denuded pastures to recuperate.

Fig 2. Jheel can be spotted due to thickets of indigenous trees, seen above Desi Baval or Babol tree indicating presence of drinking water.

Shape of the horns as codes for identifying pure Banni bloodline livestock. A pure bloodline Banni buffalo will have tightly coiled horns. The shape of horns is a natural code to identify whether the buffalo is pure breed or cross breed. Pure bloodline Kankrej cattle on the other hand will be tall with long and thick horns. (see Fig. 3).

Fig 3. Kankrej cattle, with its prominent horns. Buffalo calf on the left can be identified as pure bloodline Banni, owing to the coiled horns. While one on right is a cross between Jafrabaadi and Banni buffalo, one can tell from the horns that spread backwards.

Natural codes that point to good health in Banni buffalos:

• Horns tightly coiled in perfect concentric spiral

• Thin skin

• Ratio of length of legs to the size of hooves

• Firm udders and tits

• Fachar Aakar: Should be smaller in the front (head) and larger at the back, this shape is especially suitable for hassle free deliveries

• Prominent milk vein

• Body height should be proportional to body length and weight. Feet shouldn’t be too long or short.

• Codes for cattle are similar except, horns of Kankrej cattle grow out long and thick.

(see Fig. 4)

Fig 4. Codes for a good Banni buffalo manifest here.

Natural codes of good health in Kachchhi camels:

• Good height-body

• Hump slim and heightened

• Small chest pad • Head and mouth raised upward and looking forward.

• Erect ears • ‘Chavro’ colour (blackish brown)

• Scrotum uplifted (male), prominent milk vein (for female)

(see Fig. 5)

Fig. 5. Codes for a good Kachchhi camel manifest here.

Dung as a code:

Change in colour or odor of the livestock manure is also a code of ill-health. The paths animals have taken in the pastures while grazing can be identified by the series of animal droppings. Depending upon how fresh or dry the dung looks, one can gauge how long ago livestock must have passed. From the kind of dung, one can identify which livestock animal cow, buffalo, horse, sheep, goat or camel has been grazing in an area.