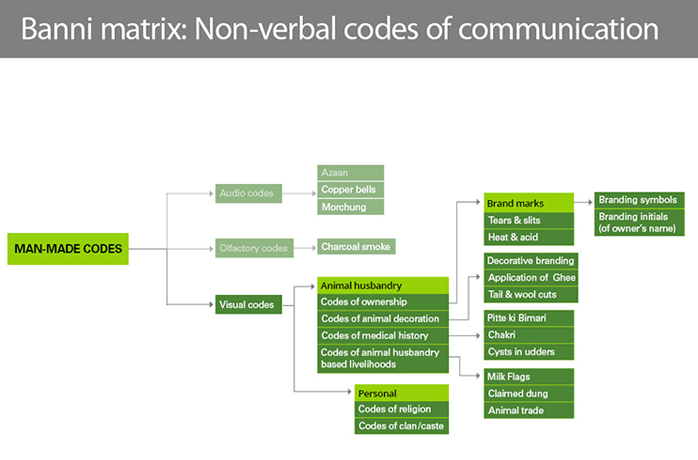

Man-made non-verbal codes of communication in Banni can be further classified into audio, visual and olfactory codes. I will discuss two verbal codes of communication at the heart of animal husbandry at Banni as well towards the end of the paper.

Pastoralists in Banni claim that Maharao of Kachchh bequeathed Banni as a commons to their ancestors who were nomadic pastoralists originating from the Sindh region in Pakistan. It was given in their custody with the condition that they protect the grassland ecosystem and share it communally for grazing and not use it for agriculture or divide it up into private property. They have since used Banni only as a pastureland and discouraged any farming or private land holding within it.

As a result Maldharis in Banni follow practice of nomadic pastoralism. It comprises of some interesting methods. Unlike other regions where livestock (cow and buffalo for milking purposes) is tied up inside enclosures or shelters, livestock in Banni is habitual of free open grazing. That is buffalos graze freely on Banni grasses in the pastures all night (cows need some degree of supervision) and return to their respective owners’ homes- twice a day in the morning and late afternoons to eat protein and mineral rich cattle feed and drink water. The herder milks the animals as they are eating food from the bags tied around their necks. Most of the times, the buffalos come back on their own, without any issues. But there are about 85,000 animals in Banni. To prevent them from getting lost or from entering each other’s herd Maldharis have made use of marks or codes as one may call them to satisfy purposes such as ownership identification, decoration, health treatments of animals.

Audio codes:

• Azaan as an audio code:

The Azaan that takes place five times a day in the mosques was and continues to be a code that allows for schedule keeping. This was especially useful when having a watch was uncommon and cell phones were unheard of.

• Chiming copper bells as a code:

Each herd of cattle or buffalo has a dominant female with the biggest copper bell around her neck other animals of the herd normally graze in the hearing distance of this dominant female. Each day, early morning when most people are indoors sleeping, thousands of copper bells chiming together in unison become the alarm clock for pastoralists to wake up and get ready for feeding and milking their cattle. This code was especially handy when there were no watches. (see Fig. 6)

Fig 6. Dominant female of the herd wears biggest bell.

• Music of the Morchang as an audio code:

It is an interesting sight to see, herders and shepherds in Banni playing Morchung or shepherd’s harp as they graze their sheep-goat. The music from the harp is not only meant to entertain the shepherd, but also creates an audio boundary for the livestock- to graze within.

Man-made Olfactory factory code in Banni:

• Charcoal smoke as an olfactory code:

Charcoal-making, the supplementary occupation in Banni to animal husbandry although environmentally degrading has proven to be lucrative for locals. The number of charcoal kilns is a code of disposable income of the family. Also if one loses way in Banni, charcoal smoke can guide one to the nearest village. (See Fig. 7)

Fig. 7. Animal husbandry is supplemented by charcoal-making in most areas of Banni. Charcoal smoke is a signifier of a village being nearby.

Man-made Visual Codes related to Animal Husbandry in Banni:

• Codes of ownership identification on livestock:

Brand marks:

The livestock population in Banni outnumbers the human population of 17,000 by five times. Plus livestock grazes freely in the pastures, unsupervised and travels long distances in search of fodder sometimes; a system of owner identification marks has evolved to prevent loss or confusion of animals.

a) Tearing/ slits/ holes in the ears:

Livestock keepers of Raysipotra clan in villages of Bhirandiyara and Ghadiyado make a tear with blade at the bottom of both ears of their animal- cow or buffalo. (See fig. 8) This tear which leads to a semi-circular, arc like open hole in the ear is locally called ‘Kakkar’. Yet another clan called Halepotra, make similar holes but at the top of each ear. (See fig. 9)

Livestock keepers from villages close to Banni such as Jhurra and Sumrasar often send their animals to graze in Banni. These villages also have their own distinct marks. Livestock from Sumrasar has two holes in middle of the left ear and one hole in middle of the right ear, while that from Jhurra has two tears at the bottom of both ears.

Fig. 8. Code of Rayspipotras of villages Bhirandiyara and Ghadiyado: A hole at the bottom of both ears.

Fig. 9. Code of Halepotras of village Hodka: A hole at the top of the ear, on both ears.

b) Branding using heat or acid and follow-up practices:

Livestock keepers also use symbols. Currently these do not have any particular system; any herder comes up with a mark of his own having ensured that it does not resemble the marks of other herders’ in the vicinity. Then these marks are branded onto the livestock using hot branding irons or branding irons or a wooden stick dipped in acid.

These marks can be further divided into two categories:

• Branding symbols

• Branding initials (of names)

• Branding symbols:

Amongst 8 pastoralists I interviewed only two were found to be using a symbol (made of shapes not words). One Jat pastoralist and a Halepotra pastoralist in western and Central Banni were coincidentally using symbols that resembled spectacles, with only a slight variation. (See fig. 10 and 11)

Fig. 10. Spectacle like symbol of Jat clan, village Sarada.

Fig. 11. Spectacle like symbol of Halepotra clan, village Erandavalli.

• Branding initials of names:

These days, many pastoralists brand initials (or full names in case of short ones) onto the livestock. Earlier, Gujarati was the chosen language, currently English initials are wide spread. But when there is a common code, example alphabet ‘M’ resulting from common names like Meherali, Mirmohammad or Mohammad and Mujeeb- the position of the branded alphabet ‘M’ on the body also becomes the code for identifying owner of the animal. Pastoralists with their mutual understanding decide upon unique positions for each person. Often names are used in addition to the shape symbols. (See fig. 12.1 and 12.2) Maldharis follow this system so that lost cattle can be located using cell phones, by calling other Maldharis in the vicinity. Codes make it easy to locate, describe, and identify an animal.

Fig. 12.1. Iron rod used as branding iron.

Fig. 12.2. The impression resulting from the branding iron

Process of branding:

The process of branding has undergone a change due to environmental and socio-economic factors. Initially for centuries together, Banni pastoralists were cattle breeders and would supply good quality bullocks to farmers in Saurashtra and Kathiawad region. But after Prosopis Juliflora was planted in early 1960s, it had an adverse impact on health of cows. Soon Banni pastoralists switched from cow rearing to buffalo rearing. Cows a Maldhari pointed out ‘come in variety of models’ that is different colours and body patterns and branding it is not a necessity. But buffalos are by and large black, which could create confusion and hence branding buffalos (although cruel to the animals) became a practice.

Earlier Banni economy of primarily breeding and selling animals, changed into dairy based (selling milk) economy in around 1980s. Prior to that, buffalos were being branded with hot iron rods. With setting up of dairies in Banni, Pastoralists have started using acid (dairies sell acid that is used for fat testing at milk collection centre) to brand buffalos.

My interviews with pastoralists indicated that heat scars only the skin surface (but does not leave a deep wound); on the contrary acid seeps through skin leaving open wounds that often either get infected or crows peck at them causing great pain to the livestock. To heal any possible infection arising due to acid branding and to prevent crows from pecking on the wounds- Maldharis ‘clean’ the wound with kerosene and in some cases pack it with a home-made ointment. Contextual inquiry in the villages revealed that this ointment was chemical mixture (black powder) from used pencil batteries mixed with mustard oil (See fig. 13).

However, its still a question of investigation that how are the affects of such chemicals on animals and what effect it would have on human health if it enters the food chain via milk.

Fig. 13. Powder from used battery cells mixed with mustard oil used as ‘tattooing ink’ to pack the open wound resulting from branding with acid.

Non-invasive animal identification codes:

a) Coloured horns a code for ownership identification:

Pastoralists of Banni (mostly Muslim, with exception of few Hindus from Meghwal Marwada community) claim Hindu pastoralists from villages outside of Banni paint horns of cattle during Diwali for celebratory purposes. Also herders/ farmers, mostly Hindu from rest of Gujarat leave their livestock for grazing with Banni pastoralists. It is these people who colour animal horns as a code for easy identification. But Banni is full of thorny shrubs and when the livestock goes grazing, the colour wears off in less than a month.

b) Colour on bodies as a code for ownership identification in sheep and goat:

Livestock keepers who keep sheep and goat put colour on their bodies. (See fig. 14)

Fig. 14. Colour coding sheep for easy identification.

c) Branding using accessories:

A Jat pastoralist who owns only cows- Kankrej cattle (some 300 cows) says cows need to be supervised when they graze and are never left alone like buffalos. Hence branding a cow is not needed; using accessories around their cattle’s necks for identification is sufficient. Plus accessories do not hurt like branding and hence are a better option for cows, he pointed out. (See fig. 15)

Fig. 15. Accessories like these are preferred as identification codes for cows, instead of heat or acid branding them.

Dairy Tags:

Dairies tag livestock purchased on loan with a yellow tag. (See fig. 16)

Fig. 16. Dairy tag. In case of death of the insured animal, Maldharis are supposed to report to the insurance agency with the animal’s ear that bears the insurance tag.

Codes of animal decoration:

a) Branding livestock for decoration Pastoralists may at times brand animals on their faces (in cattle) as well as face and forelegs (in camel) to negotiate a better price for their animal. Healthy animals that look attractive as well fetch more money for the pastoralist. (See Fig. 17)

Fig. 17. Here, brand marks are used as decoration, not for identification necessarily.

b) Smearing animal bodies with ghee Pastoralists apply ghee (clarified butter) to buffalo’s body in order to make the buffalo’s coat shine. Especially in case of breeding bulls, a glowing skin creates the perception of vigor and vitality and enables pastoralist to negotiate a better price for the animal. A buffalo coated in ghee is a code of it either being in the health competition (organized during animal buying and selling fairs) or for sale. (See Fig. 18)

Fig. 18. A buffalo smeared with Ghee is an indication that it either in a competition or on sale.

Brand marks as codes of medical history of livestock:

Before arrival of dairies and thereby veterinary doctors in Banni, Maldharis relied on their traditional knowledge for treating animals in case of diseases. Of many traditional treatments, one is branding animals in specific places on their body to cure certain diseases.

a) Pitte ki Bimari (disease of the gall bladder): A cross branded on left hip. (See Fig.19)

b) Chakri (Trypanosomiasis): branding on forehead

c) Cysts in udders: branding on top of the body towards rear.

Fig. 19. This brandmark indicates the animal has had an illness of the gall bladder.

Codes associated with animal husbandry based livelihoods:

• Milk flags:

White plastic hanging from Ganda Baval plants by the roadside are an indication for the driver of the milk van to stop and collect milk. (See Fig. 20)

Fig. 20. Milk flags are a handy code for the milk collection vans of the dairy.

• Dung with a stick:

Women and children in Banni are involved in collection and sale of dung for its use as manure. Given the animal population of Banni, dung is omnipresent. However it can be collected only when it is semi-dry. People use sticks to claim the dung, so that others don’t collect it. (see Fig. 21).

Fig. 21. ‘Claiming the dung’ is an interesting method, first spotted in Daddhar village, Eastern Banni.

• Negotiating price of livestock:

In Banni, if a buyer particularly likes an animal, he either goes in through a broker or directly approaches the animal breeder himself. To negotiate a price for the animal in question without others in the vicinity finding out about it, the buyer and the animal owner cover their hands with a handkerchief and negotiate in a coded. If only one finger is pressed then it stands for one lakh rupees. If many fingers are pressed together (but not the whole hand or thumb) each finger stands for ten thousand rupees. If the whole hand is pressed at a time it represents fifty thousand rupees. Thumb stands for rupees five thousand. And once the price between buyer and seller is fixed and the deal is sealed, the buyer gives seller hundred rupees as token money and pays the actual price in three subsequent annual installments. (See Fig. 22)

Fig. 22. A buyer from Ahemdabad, negotiating price with the Maldhari, at Pashumela 2011.