Search

- yohoho

- unblocked games 77

- unblocked games 8

- unblocked games 2

- unblocked games for school

- unblocked games world

- retro bowl

- unblocked games

- unblocked games premium retro bowl college best unblocked games unblocked games

History of Block Making in Pethapur:

Though written documentation is sparse, the craft of blockmaking is believed to have taken root in Pethapur sometime in the 18th century. The art was brought to the village by people of the Gujjar Suthar tribe who were carpenters by profession constructing buildings, making furniture, agricultural implements, etc. While their regular work was seasonal, block-making provided a more stable, year-round income source and had better returns. The low cost of living in Pethapur and the availability of more space for workshops are other reasons that may have contributed to the craftspersons settling in Pethapur (Trivedi, 1961).

The block-makers chiefly serviced the Ajrakh block-printers of Kutch and the Saudagiri printers of Ahmedabad, both of which are characterized by different kinds of motifs adept at creating the distinct styles of the two traditions. However, their skills and dexterity also extended to creating images of village life and naturescapes that looked like those painted by a brush (Bhatia & Bhatt, 2017). Examining old prints in possession of surviving crafts persons also hints at Western influences, with motifs of flowers and depictions of people with more in common with prints from 18th century England than more traditionally Indian designs.

This might be explained by the fact that while block-makers did design their motifs and patterns for printers to select, they acted as skilled labor for hire who carved blocks out of the prints that were supplied by the printers based on what the market demanded, and as such, provided blocks to many printers based in different block-printing centers due to their reputation as the best of the best.

At its peak, the craft of block-making was practiced by anywhere from 200 to 300 people working in large workshops together instead of small spaces at home now. According to local legends, Pethapur was known to have reverberated with the sounds of metal clicking on wood from the craftspersons' activity. Accounts from Dahyabhai Prajapati and Govindhbhai Prajapati, the senior-most craftsmen in the village, suggest a progression system for young men who wished to pick up block-making as a trade. Apprentices would learn by observation, work directly with their mentors, and serve their attendant needs.

Workshops had often resembled a production line, where different craftspersons would work on a block at different stages and pass it down to the next person, though it was just typical for one to work on a single block from start to finish. Families that owned the workshops employed skilled family members for etching and engraving, while hired workers cut the blocks to size, ground the blocks, and prepared them for engraving. Unfortunately, women had never been involved in the craft, and no account would suggest as much.

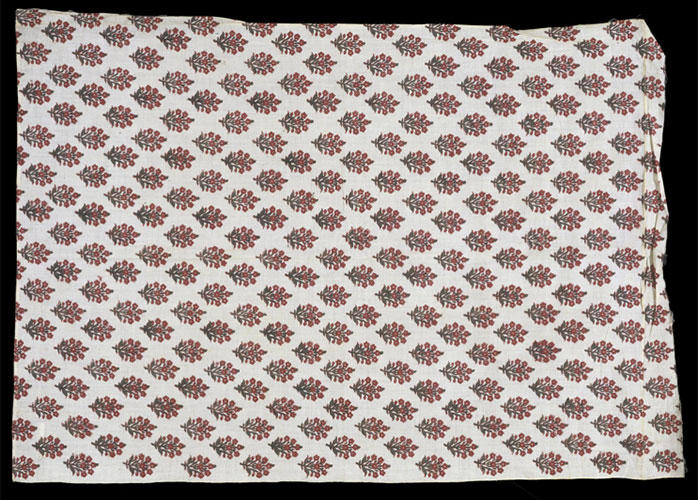

Block-Printed fabric from Sanganer, Rajasthan from ca. 1850 in possession of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. The description of the exhibit mentions that "the most highly esteemed blocks are traditionally those made in Pethapur in Gujarat."

The Decline of Block Making in Pethapur:

The craft thrived for a long time, making the village of Pethapur known for this craft until the mass-scale screen and machine printing arrived in the mid-20th century. Scores of textiles mills - predominantly machine-driven – cropped up in places such as Ahmedabad, which provided cheaper and faster production means. Both the block-printing and block-making communities experienced insurmountable competition due to the pace and volume at which industrial mills produced textile products, leading to the twin decline of textile traditions such as Saudagiri in Ahmedabad and that of its sister-craft of block-making in Pethapur (Bhatia, 2014).

According to Bhatia (2014), another cause of block-making's downfall may have been the rising cost of wood that made it difficult for block-makers to afford the raw material needed for their work. This would surely have led to increases in the price of block-printed textiles, resulting in less demand than machine-printed textiles, which led to a decrease in the work available for block-makers, thus triggering a negative feedback loop.

From a high of 300-odd artisans in the village at its peak, only a handful of them remains today. According to a census report published in 1961, at least 132 craftsmen were practicing in the village. Still, today there are only 21 of them, a number that keeps dwindling due to the craft's lack of economic opportunity. What remains of the craft paints a sad picture of lack of enough initiative from the government and recognition of handicrafts by the Indian market. Efforts are underway by patrons and people who appreciate the craft to preserve it through documentation efforts and protecting the work of artisans and giving them due recognition, such as the recent Geographical Indication (G.I.) Certification of block-making in Pethapur courtesy of Gujarat Council on Science and Technology.

Shri Dahyabhai Prajapati, 78, is one of the seniormost and last remaining master craftsmen in Pethapur, a living vessel for knowledge of this craft.