Perception of motion is described as the perception of a sequence of changes. The capacity to detect motion is irrefutably advantageous for survival as it is closely tied to the perception of food and threat. The ability to perceive motion is so fundamental that it seems to come naturally to humans and other organisms. We sense motion when something travels across our field of vision. Unique physical structures have evolved in humans to help with the experience of motion. Your eye muscles, for instance, enable you to move your eyes swiftly and smoothly in all directions. Your head has a roughly 180° range of motion. By moving only your head and eyes, you can physically observe objects throughout a 360-degree field using these structures.

The image of an object moves across successive sites in the retina as it moves across your field of vision, and the experience of motion results from a pattern of successive cell stimulation. To keep a moving object in focus, one has to move their head and eyes; while doing so, there is a feedback system that alerts the brain of the head and eye movements.

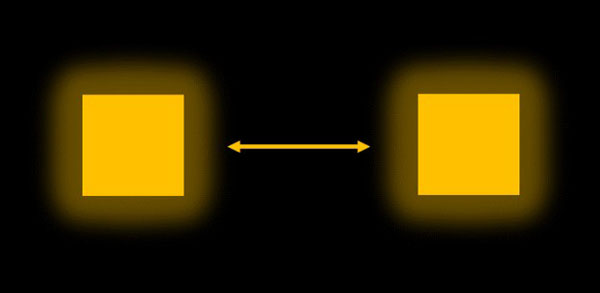

An object's actual motion is known as real motion. For example, when a car passes by or a bug crawl across a table. However, numerous techniques exist for creating the perception of motion from a stimulus that is not moving. Illusory motion is the term used for perceiving motion when none exists. Apparent motion is the most well-known and researched sort of illusory motion. For example, look at the video below; it seems like the square is moving towards the right. However, they are two stationary objects.

Figure 6.1.a

Source: Sruthi Sridhar

Max Wertheimer demonstrated that when two stimuli at slightly different places are alternated with the proper timing, an observer will interpret one stimulus as smoothly transitioning between the two sites.

Figure 6.1.b

Source: Sruthi Sridhar. Recreated from Goldstein, 2010

Since there is no actual (or true) motion between the stimuli, this perception is known as apparent motion. This is the basis for the motion in entertainment and advertising-related moving signs, television, and movies.

There are two types of illusory motion: induced motion and motion aftereffects. Induced motion is the phenomenon that occurs when an object moves (the larger one), making one perceive that the smaller stationary object is also moving. The moon, for instance, always appears motionless in the sky. However, the moon may appear to be racing through the clouds on a windy night. In this instance, the smaller, stationary moon seems to move because of the movement of the larger object (movement of the clouds covering a larger region). When someone watches moving stimuli for a long time and subsequently focuses on a stationary object, they experience the motion aftereffect. The object will seem to move in the opposite direction from the moving stimuli.

Some stationary and repeated patterns create the illusion of motion. You can usually enhance the illusion by moving your eyes around the figure. The illusion tends to fade away or even totally vanish if you keep your eyes motionless. For instance, the "snakes" in Akiyoshi Kitaoka's Rotating Snakes illusion seem to be rotating when in reality, except for your eyes, nothing is moving. The animation will slow down or even halt if you focus on one of the black dots in the centre of each "snake." (See illusion here: http://www.ritsumei.ac.jp/~akitaoka/index-e.html).