In the previous section, we discussed several types of camouflage. As a reminder, there are four types of camouflage: blending, countershading, mimicry and disruptive. However, there is another type of camouflage known as contour-distorting camouflage, which is based on distorting a figure's contour rather than simply blending into the background. This type of camouflage is effective in breaking up the figure's shape by essentially distorting the contours of the figure's silhouette. In other words, such patterns help decrease the animal's perceptibility in the natural world. Such contour-distorting camouflage manifests itself throughout nature in the form of "boldly contrasting patches of colour that mask the contour of their wearer and break the animal up." Contour-distorting camouflage is most successful when combined with backdrop-matching camouflage and a perceptually complex figure and background. That is why it is far more difficult for predators to target any individual zebra as prospective prey when they stand or move in groups.

Contour-distorting camouflage diminishes our ability to see objects since it frequently uses perceptually complicated figures. One of the defining characteristics of Cubism, as seen in Pablo Picasso's "Portrait of Wilhelm Uhde," is contour distortion. The intention was to blur the lines of figure-ground separations by distorting contours. The forms in the movements are made such that it combines with the space around them or with other forms, where tones or planes blend into one another, and outlines coincide before unexpectedly re-emerging in new relationships.

Figure 3.4.a

Source: Portrait of Wilhelm Uhde © ARS, NY. Photo Credit: Bridgeman-Giraudon/ Art Resource, NY

Following this movement, Guirand de Scévola recruited Cubist artists in World War I to "obliterate objects" and prevent the recognition of objects. Numerous soldiers who had previously worked as artists in the civilian world were tasked with camouflaging. The "laws of organization" that Gestalt psychologists had proposed were also developing simultaneously.

Kurt Gottschaldt created The Embedded Figures Test in 1926. The test was inspired by the cognitive challenge of identifying figure-like entities embedded in perceptually complicated combinations. This test measures our capacity to cognitively separate figures from their background and identify recognizable shapes "hidden" in intricate designs.

Multiple practical examples use the theory of embedded figures in everyday life. From finding hidden "Disney" throughout Disney theme parks to hidden picture puzzles such as I-Spy or Spot it that we play with kids to the book "Where's Waldo?" use the same idea of embedded figures. It is also used in word search games where we have to find the actual word in a grid of scrambled words.

Figure 3.4.b

Source: Sruthi Sridhar

Embedded figures are images that allow one to visually identify and distinguish local components within a larger configurable shape or to select a simple figure from a bigger image. When the lines of a simple figure perceptually belong to a broader picture, it becomes more challenging to distinguish between the two.

The explorations below attempted to comprehend the various methods of figure embedding and explore a few different Gestalt laws. The first exploration is a simple geometric one with a face embedded within the polygons. In this image, the eyes can visually locate elements of the face at a global level.

Figure 3.4.c

Source: Lakshmi Chandran

A "busy" design undermines the capacity to recognize an object's shape, jeopardizing the perception of the object's wholeness. An object may no longer appear to be a single, perceptually cohesive entity if it has a lot of "interior detail that is more salient than its edges," leading potential perceivers to believe that they are witnessing multiple objects. While a figure may no longer be viewed as a separate entity when it is arranged to blend or match its surrounding context, altering a figure's contours makes it more challenging to recognize it as a single thing.

On the contrary, finding the embedded figure becomes more challenging as the image becomes simpler. In the exploration below, there is nothing but branches. The exploration focused on creating a Hand emerging out from the thin branches. But one can identify it only after being pointed out. The image is much harder to pick out as the details are fewer.

Figure 3.4.d

Source: Lakshmi Chandran

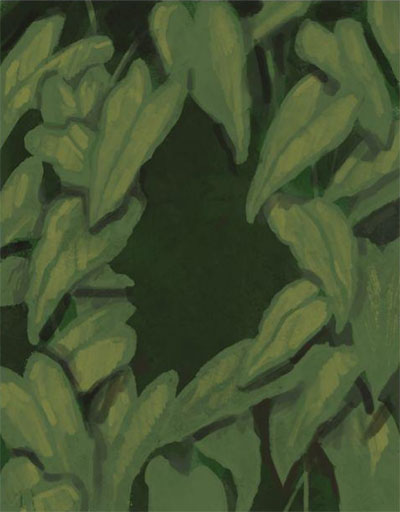

As discussed before, figure-ground segregation is the ability to identify the boundaries or contour in an image. In the image below, a boundary appears between the leaves and the dark shadow within to create a side profile of the face. The change in the quality of luminance here allows us to identify the face due to depth. This exploration uses a range of greens, so the embedded figure tends to blend in with the ground.

Figure 3.4.e

Source: Lakshmi Chandran

The exploration tried a contrasting colour to understand the effect of embedded figures. Through this, it is clear that the figure to be embedded/ hidden stands out very clearly, i.e., the figure stands out from the ground and is no longer confounded. And in this image, the area occupied by the figure also overpowers the effect.

Figure 3.4.f

Source: Lakshmi Chandran

Original figures can be downloaded here:

• Embedded Figures......