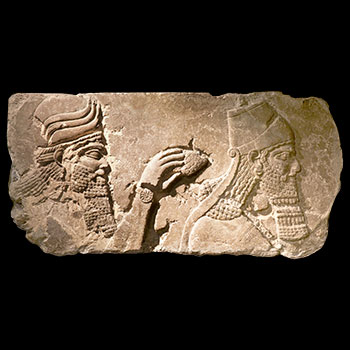

The present collection of reliefs from Ancient Assyria (c. 900–600 BCE) at the museum comprises 12 alabaster reliefs from Nimrud. Of them 8 are from the palace of Ashurnasirpal II, 3 from the central palace of Tiglath-Pileser III, and one from the palace of Sargon II at Khorasabad. Out of these 10 slabs were gifted by the British resident at Baghdad, Henry Rawlinson, to the Governor of Bombay, Sir George Clerk, in I847, who in turn gifted them to the city of Bombay in 1848. These were prominently displayed in the Economic Museum, which existed inside the Town Hall in Bombay throughout the 1850s, and are now housed in the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sanghralaya (CSMVS). There are two extra objects. These may belong to the shipments of antiquities of ancient Assyria from Basra, which were on their way to London between 1846 and 1848. The objects were all collected and found during the excavations at Nimrud (near Mosul, Iraq) by the British explorer and diplomat Henry Austen Layard. The Asiatic Society of Bombay took the chance of displaying the antiquities. Layard later accused Bombay of vandalism and theft of his objects, which were strongly refuted. As the reports of The Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce reveal, The Asiatic Society took great care, and had received the objects with enthusiasm and scholarship.