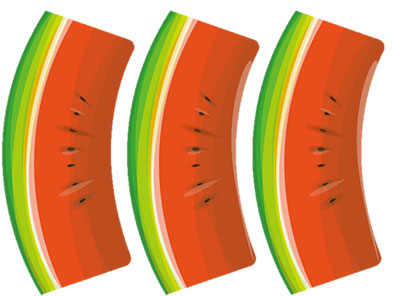

Figure 7.3.a

Source: Harmeet Kaur

There are three slices of watermelon in the picture above. Which piece looks the biggest? If you are like most people, the slice on the far left will look the smallest, and the middle portion will look smaller than the slice on the far right. This is the Jastrow illusion. When two similar figures are positioned next to each other, the Jastrow illusion is created. Even though they are both the same size, one appears to be larger.

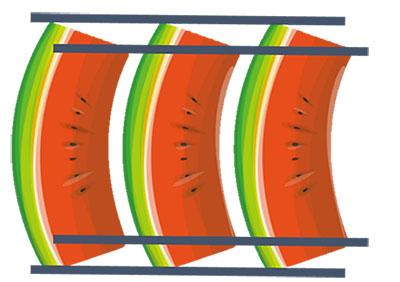

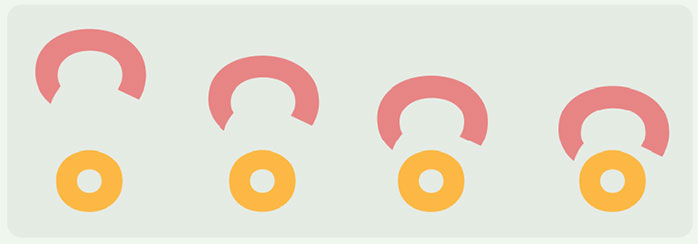

Figure 7.3.b

Source: Harmeet Kaur

The Jastrow illusion was named after Joseph Jastrow, an American psychologist who first identified it in 1889. Jastrow illusion is also known as Wundt area illusion, Wundt – Jastrow illusion or Ring – segment illusion. When two curved forms with identical measurements are put next to each other, the Jastrow illusion occurs. When looking at the two shapes side by side, one appears to be substantially larger than the other. The Jastrow illusion still occurs when the two shapes' positions are reversed or changed in orientation.

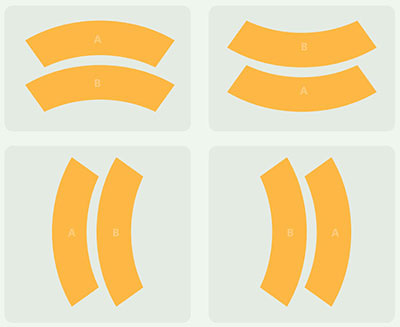

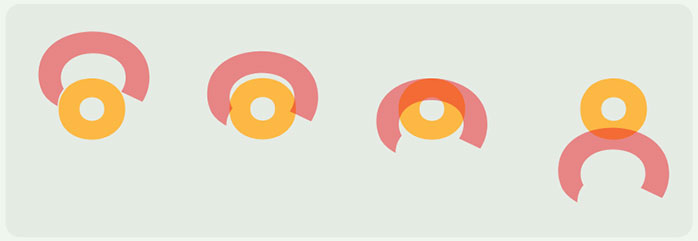

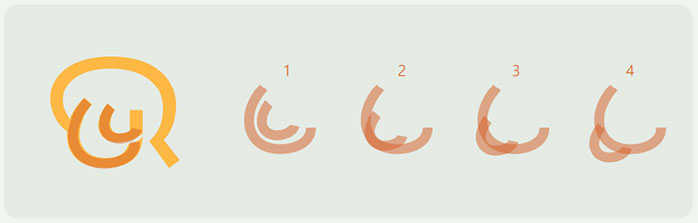

Figure 7.3.c

Source: Amit Patjoshi

Two identical figures, "A" and 'B' are placed adjacent to each other, and both figures are then rotated in increments of 90 degrees. As it can be observed, the Jastrow illusion still holds in place despite the objects' orientation.

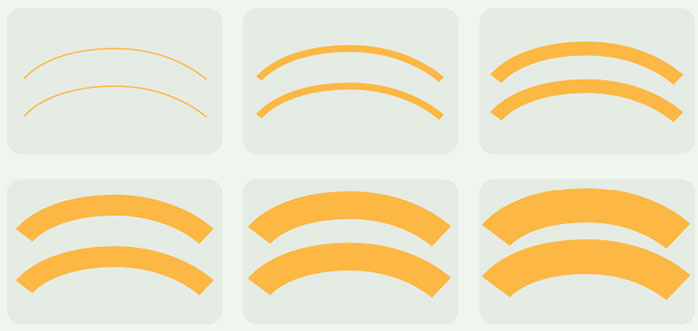

Scientists are still puzzled as to why one of the figures in the Jastrow illusion appears larger than the other. Researchers have observed similar results using a variety of geometric shapes, such as trapezia, parallelograms, and diamonds. But does it work better in curved shapes or straighter shapes? The figures below show two identical shapes with uneven sides curved from the centre. The illusion still occurs when the shapes are straight but are less prominent. The illusion becomes stronger as the curve increases. The brain is tricked into interpreting one form as long and the other as short since the shorter side of one figure is close to the longer side of the other; however, it is unclear why.

Figure 7.3.d

Source: Amit Patjoshi

How about the thickness of the shape? Does the extent of the illusion change with the thickness? The exploration below changed the thickness of two identical lines from 1 point to 25 points, and they were placed next to each other. The illusion appears to be almost non-existent with thin lines. However, as the thickness increases, the illusion becomes more prominent.

Figure 7.3.e

Source: Amit Patjoshi

Although there are a couple of explanations for the Jastrow illusion, scientists are still unable to reach a consensus. One theory relates to how the mind perceives the 2D images on the retina in the context of a 3D world. Another idea is that the mind can only focus on a small field of vision, which is then reconstructed by our consciousness. The most prevalent explanation is that the contrast in size between the large and small radius confuses the brain. The long side makes the short side appear even shorter, while the short side makes the long side appear even longer. Another explanation is that the lower figure looks to be longer because the longer side contrasts with the shorter side of the figure. The brain cannot overlook the length of the sides when evaluating the areas of the shapes, and the perceived areas are frequently relative, despite our attempt to interpret them as absolute.

The illusion is often observed in the real world. For example, when two curving toy railway tracks are kept vertically, the lower one looks larger, even though they are identical. However, one area where the illusion is often overlooked is in the fonts of Indic scripts. In comparison to Latin scripts, Indic scripts have a lot more curves. Because of their origins, the characters have these curved structures. These characters were inscribed on palm leaves, which had vertical fibres. These vertical fibres made writing with straight strokes extremely difficult as the palm leaf would tear from the direct force applied by the writing instruments. The Odia script may find the Jastrow illusion in numerous places, which is one of the scripts with similar beginnings. Some examples are illustrated below.

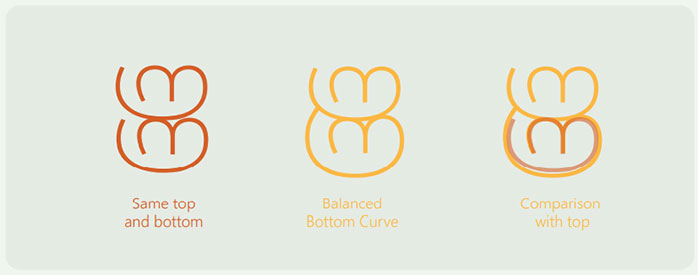

The image below exhibits the letter 'La' in Odia. The letter is typed in the font Noto Sans Odia by Google's Noto project. The line above the letter is the diacritic sign of 'e.' This is an excellent example of the Jastrow illusion becoming prominent as the type of font differs (thin, regular, or black). Even though the letter is written in the same font, the accent seems smaller and heavier than the alphabet itself as the thickness increases.

Figure 7.3.f

Source: Amit Patjoshi

One explanation for the illusion provided previously is the presence of a stark contrast between the shorter and the longer side. Therefore, the longer side seems to be much longer and vice versa. This concept of Jastrow illusion can also affect the perceived size of curves in characters with two or more curves. Even if the curves are of different sizes, the example below explores the size perception of these curves concerning their positioning. The Odia letter' ଚʼ (ca) has two curves on top of each other. As seen in the example below, positioning the larger curve below the circle makes it seem much larger than when positioning the larger curve above the circle. When a smaller circle is placed above the larger curve, we have a reference point of how small the circle is; therefore, we tend to judge the curve to be larger than it is. Because as the smaller side of the top curve interacts with the lower circle, it needs to be made larger to look normal-sized.

Figure 7.3.g

Source: Amit Patjoshi

Figure 7.3.h

Source: Amit Patjoshi

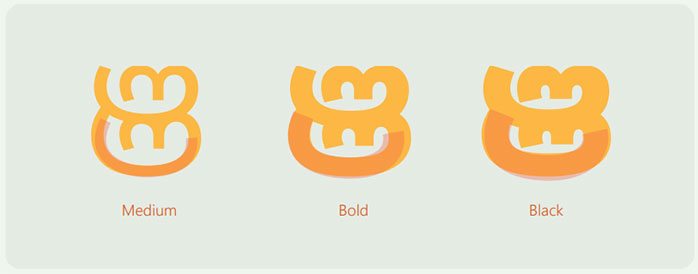

The width of the top curve is affected by the weight of the letters. These letters are written between the cap height and the baseline, and the lower circle and upper circle are drawn at the same height. When the letter weight is increased, the weight in the bottom circle and the top curve on the inner side increases. Behind each letter, transparent red boxes of the same width indicate how the top curve is subtly widened to counter the illusion.

Figure 7.3.i

Source: Amit Patjoshi

Unlike the above letter' ଚʼ (ca), which has a direct interaction with the curves, letters like 'ଞʼ (nya) have the same form that is repeated in its formation. There are additional elements in this letter other than the curve. Therefore, to achieve balance, the lower part of the letter is made a little bit larger. Jastrow's illusion in this example seems to hinder the balance of a letter. Therefore, the lower part has to be modified to counter the illusion and achieve a sense of balance.

Figure 7.3.j

Source: Amit Patjoshi

One can notice the difference in the curve in other weights. Interestingly, as the letter becomes heavier, the difference gradually decreases.

Figure 7.3.k

Source: Amit Patjoshi

Some letters, such as the letter' ଭʼ (bha), also have the effect of a curve branching out. Although the curves are not the same size as the original illusion, the illusion persists in the impression of their relative sizes. As shown in the investigations below, the difference in size perception between 1 and 2 is astounding.

Figure 7.3.l

Source: Amit Patjoshi

Similarly, the graphic below depicts the Odia letter 'La' with two different signs: the vowel sign 'e' and 'Chandra Bindu.' The Chandra Bindu appears to be substantially smaller at first glance. However, as we flip the 'e' sign, they seem to be about the same length.

Figure 7.3.m

Source: Amit Patjoshi